Chester Mystery Plays

The Chester Mystery Plays have become a rare and treasured part of Britain's cultural heritage, now only performed every five years (June/July 2018, 2023, etc.), with a cast of hundreds including choirs and the gawping crowd! There are very many ways of examining the plays, this article looks at links between the subject-matter of the play and the trade of the guild which performed it. The puzzle is whether the assignment of plays to appropriate guilds was a definite choice, or whether the guilds took the plays in the hierarchic order of the guilds and (perhaps only slightly) adapted the scripts to reflect their own interests. "Order of Precedence" was once very contentious in the London Livery Companies and possibly gave rise to the English saying "At sixes and sevens". All the evidence points towards the plays not being entirely the work of one person but the accretion of varied themes and sources around a traditional set of works.

One thing worth noting about the Chester Mystery Plays is that the literature about them is vast, and, over the course of time there have been several major paradigm shifts in the understanding and interpretation of the plays. The revision of viewpoints on the plays still continues. Once it was considered that the medieval mystery plays were "the popish progeny of ancient heathen theatre and full of ungodly errors and superstition" - "a Bastard of Babylon" - buffoonery far inferior to the Elizabethan theatre of Shakespeare. Later it was realised that pre-Reformation early English theatre needed to be re-interpreted as sometimes self-disparaging art which sought to disguise itself for the sake of its own preservation and that there was not a major gulf between the Medieval and the Renaisance. With renewed interest in the plays in the late 19th and 20th Centuries, and especially performance of the plays themselves, scholarship in the area blossomed as attested by the copious reference in the "Sources and Links" below. Indeed, it is now thought that the Mystery Plays may well have influenced Shakespeare: the crucial dates are 1569 (the last performance of the York cycle), 1575 (the last performance of the Chester cycle), 1576 (the prevention of an attempt to perform the Wakefield cycle), and 1579 (the last performance of the Coventry cycle). That last date, which is often (wrongly) taken to mark the definitive end of the Corpus Christi tradition in England, is significant because it means that, up to the age of fifteen, Shakespeare was only a day’s journey away from what had been the most famous and popular of the English cycles in Coventry, drawing spectators from all over the South and the Midlands. We even hear of how members of the Mercers’ company from as far away as Shrewsbury were frequently fined for abandoning their own Corpus Christi procession and going to Coventry. The plays continued to be performed in the north of England: John Weever writes of seening them acted in Preston, Lancaster and Kendal in the early reign of James (after 1603).

Overview

Performed on wagons throughout the city, the plays could be regarded as the first organised street theatre. Taken over by city guildsmen after the monks gave up the increasingly elaborate procedure of dramatising church services for the many who couldn't follow the Latin texts, these wagon performances of amateur actors became injected with both wit and humour.

"Mystery" in this context refers "specialized skill" (ministerium, meaning craft). Very few other places found the economic or administrative means to stage such a sequence of plays, tracing their belief in divine intervention into human history, but the Chester cycle managed to thrive. It was (in medieval times) a popular annual event and the plays became a source of pride in the city. Even in the 1500s, when the growth of Puritanism led to such activities being banned altogether, Chester determined to continue and managed to stage its plays longer than anywhere else in England - much to the fury of some of the local clergy. A near-complete text of 24 plays and some fascinating documentation of actual medieval performances in Chester survives today.

The origin of Mystery Plays may go back to 1210, when, suspicious of the growing popularity of miracle plays, Pope Innocent III issued a papal edict forbidding clergy from acting on a public stage. This had the effect of transferring the organization of the dramas to town guilds, after which several changes followed. Vernacular texts replaced Latin, and non-Biblical passages were added along with (occasional) comic scenes.

Chamber's "Book of Days" (1863) states of them (under May 15):

- The mystery or miracle plays of which we read so much in old chronicles possess an interest in the present day not only as affording details of and amusements of the people in the middle ages of which we have no very clear record but in them and the illuminated MSS but also in helping us to trace the progress of the drama from a very early period to the time when it reached its meridian glory in our immortal Shakspeare. It is said that the first of these plays one on the passion of our Lord was written by Gregory of Nazianzen and a German nun of the name of Roswitha who lived in the tenth century and wrote six Latin dramas on the stories of saints and martyrs. When they became more common about the eleventh or twelfth century we find that the monks were generally not only the authors but the actors. In the dark ages when the Bible was an interdicted book these amusements were devised to instruct the people in the Old and New Testament narratives and the lives of the saints the former bearing the title of mysteries the latter of miracle plays. Their value was a much disputed point among churchmen some of the older councils forbade them as a profane treatment of sacred subjects. Wicklisse and his followers were loud in condemnation yet Luther gave them his sanction saying Such spectacles often do more good and produce more impression than sermons. In Sweden and Denmark the Lutheran ecclesiastics followed the example of their forefathers and wrote and encouraged them to the end of the seventeenth century it was about the middle of that century when they ceased in England. Relics of them may still be traced in the Cornish acting of St George and the Dragon and "Beelzebub".

One fact often overlooked about the plays is that they were performed along The Rows, so people would be watching them not only from the street but also both from the Rows and from rooms above, particularly the chamber over the Rows. The fact that well-to-do sixteenth-century Cestrians rented out window seats in those apartments during the Whitsun play performances testifies to how highly locals valued the view of the wagons from above.

Much ink has been spilt on the subject that the Mystery Cycles hide some deeper and over-arching meaning. There is sometimes a tendency in historical analysis to import present day issues into prior situations. A few examples suffice to illustrate this.

One such theory is that the Chester Plays have a sub-text about the social and even physical relations between men in a male dominated society where women only have the role of child-bearing and are otherwise merely a source of grief (Eve brings about the downfall of Adam, Noah's wife is a problem he doesn't need and Mary causes Joseph worry due to her "infidelity"). That supposed sub-text would see the plays as some kind of reference to a "homo-social" society, where men must know their place as regards other dominant male figures. Such analysis can perhaps be taken too far. Fitzgerald for example (see links) suggests that Lucifer is a Tanner because the Tanners led the Corpus Christi procession "carrying lights", and that the Tanners were somehow "untouchable" and disenfranchised because of their profession. Such an extreme view may not be needed to understand the plays as distinct from the essentially patriarchal elements of the society they were found in. In fact, during the period 1558-1625 Chester was ruled by 71 mayors and of these 8 or 11-26 per cent can be identified as leather craftsmen. These 8 comprised 6 glovers, including Robert Brerewood who was mayor on three occasions, and 2 tanners. If the attainment of mayoral rank be viewed as an indicator of social and economic influence, it is clear that the much smaller group of overseas merchants was considerably more powerful than the leather craftsmen, or any other occupational group in the city. Among the sheriffs of the city the leather craftsmen featured more regularly, numbering a total of 26, or 19-11 per cent, out of 136 who held office during this period. Of these 11 were tanners, 9 glovers, 3 shoemakers, one a skinner and one a saddler.

Some Victorian writers considered that one reason the Mystery Plays were banned was because they featured "cross-dressing". In fact, it would have been more unseemly at the time for a woman to play a woman's part, than for the part to be played by a man or a boy.

Similarly, it is possible for concepts such as the similarity of some of the plays to the nature of the trades involved, maybe planted in jest, to take root and become "gospel".

This article explores possible reasons for the allocations of the plays performed by the various guilds in Chester.

History

The history of the Chester Mystery plays is complex and only a short version is given here. Other documents relating to the history are given in the "Sources and Links" below. This list is not exhaustive as only a limited number of the vast quantity of books and papers on the subject are available on-line.

Origins

The plays are traditionally dated about 1325 (or 1327), but a date of about 1375 has also been suggested. Chambers also gives a date of 1208 but notes that date may be too early. Some early writers expressed the view that they were written by Ranulf Higden (c.1280 - c.1363), author of the Polychronicon, as stated in the Prologue to the plays. Whatever their actual date, it is clear that as early as 1533 they were regarded as old beyond living memory. Chambers eventually fixed on a date of 1328 which was accepted for many years, and from which it appeared that the Chester plays were the earliest surviving mystery plays. Later reserach showed that Chambers date was based on myths and mis-statements from a proclamation from around 1531/2 and the likely date for the current text of the plays dates from around 1532 with earlier versions of some or all of the plays being performed as far back as some time before 1422.

Corpus Christi Processions

It would appear that much of the text of the plays is derived from "A Stanzaic Life of Christ" which was itself based on Higden's Polychronicon and the "Legenda Aurea". The "Life" was written by a monk of St Werburgh's, Chester, and was a clear influence on the Chester mystery plays.

The first evidence for religious plays in Chester is of a performance on Corpus Christi day 1422, which usually falls in June, but can be anywhere from 23rd May to 24th June, depending on the date of easter. The Corpus Christi feast was established by 1317 as a response to the then new eucharistic doctrine of transubstantiation. The first known celebration of the feast in England being at Ipswich in 1325. At Corpus Christi representatives of the Chester guilds walked in procession, from St Mary on the Hill to St Johns behind a consecrated "host" holding torches in a ritual known as a "light". This was not the first time such processions had been known: Palm Sunday processions existed elsewhere much earlier. In some towns there were actual "Corpus Christi Guilds". The initial form may have been a fairly simple "passion play", expanded to eleven plays and then to more (later with giants, unicorn, dromedary, lynx, camel, ass, dragon, hobbyhorses and naked boys). In 1499, the play "The Assumption of Our Lady" was performed before Prince Arthur (see: Cowper) - the ill fated elder brother of Henry VIII.

Corpus Christi Riots

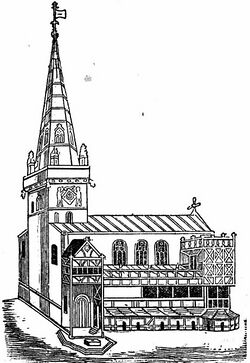

The first possible reference to the Corpus Christi procession is an inauspicious one - a record of 1399 describes a terrible brawl which broke out between the members of the guilds of the Weavers, Shearmen, Challoners (blanket-makers) and the Walkers (fullers) against their apprentices, outside of the guild church of St Peter:

- " ..and many other master weavers came with force and arms, with pole-axes, staves, daggers, and other diverse armaments, by a premeditated plan on Thursday, the feast of Corpus Christi, in the twenty-second year of the reign of King Richard the second, opposite the church of Blessed Peter of Chester. Also, those gathered together insulted William de Wybunbure, junior, Thomas del Dame, and very many others, their servants, called journeymen, in a great affray of the whole population of the city, against the peace of the lord king"

The "pole-axe" is an axe-head at end of a long pole. The design arose from the need to breach the plate armour of men at arms during the 14th and 15th centuries. Generally, the form consisted of a wooden haft some 1.2–2.0 m (4–6.5 ft) long, mounted with a heavy steel axe-head and is designed for very serious combat. This was not the only "riot" associated with the Corpus Christi procession, in June 1424 the men who took part in another Corpus Christi Day riot were said to have attacked the king's ministers at Castle Lane End: "iuxta le stouneplace que quondam fuit Petri de Thornton chivalier" - probably the stone-built house belonging to Peter the Clerk (an administrator at Chester Castle) on lower Bridge Street. These violent conflicts may have had political roots: 1399 was the last year of Richard II's reign, who had taken the title of "Prince of Chester" for himself in 1398 and was known for his "Chester Guard" - he was soon to be deposed and imprisoned briefly at Chester Castle. The 1424 riot came just after a supposed "royal visit" by Henry VI (then still a child) - it was a time of great political instability: Henry was the youngest person ever to succeed to the English throne, at the age of nine months on 1 September 1422, the day after his father's death.

Corpus Christi does seem ill-starred for rioting. In Rouen in 1560, priests and parishioners in a Corpus Christi parade broke into the houses of Protestants who had refused to do the procession honour. Corpus Christi Day was often the chance for a procession to turn into a flashpoint for assault and slaughter, as in Lyon in 1561, at Aix-en-Provence in 1572.

Corpus Christi Plays

Other famous Mystery Play “Cycles” in England were written in Coventry, York (dating from 1376 or earlier) and Wakefield. None of these play cycles should be seen as embodying some high-level theological debate without clear evidence for the same. The canon of plays in York is larger than that of Chester, as discussed in further detail below. Other English towns had Mystery Play cycles which are either lost or incomplete: these include Beverley (36 plays allocated to craft guilds), Hereford (27 plays), Norwich (13 plays) and Newcastle (up to 23). It used to be thought that the Mystery Cycles developed to maturity as "Corpus Christi Plays", but the present view is that while there was a connection with Corpus Christi it is impossible to say whether the Corpus Christi plays were plays with scripts or simple tableux - they were probably performed at the end of the procession in St Johns churchyard. Most of the texts of the plays which survive are late documents with many being compiled after (often long after) the plays had ceased being performed.

One feature of the Chester plays which is key to understanding them is that they were not performed by a troupe of professional actors unknown to the audience and separated from them by a stage setting. It was the main local streets and a significant proportion of the population of Chester itself that were incorporated into the fabric of the show, providing significant aspects of its production values, and continually shaping the performances from year to year. So far as we are aware there is no surviving first-hand description of the plays being performed and the majority of the surviving texts can only be dated to after performance of the plays had been banned. The finance records of the Guilds show something of what they spent on the plays, but the records leave many gaps. It is rather like turning up at a theatre long since closed, finding some of the receipts of what the organisers spent and some versions of the scripts recorded by long-dead fans who were never sure of the evidence on which they based their work. Staging the plays was a central part of the guild activities in Chester. Perhaps even playing the part of a competitive team-building exercise.

Performance

The plays were originally performed over two days. The event proved so popular that still later, around 1521, it was stretched to cover the three days of Whitsuntide, Whit Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday. The guild accounts of expenditure give us a fairly detailed picture of the sequence of events leading up to the performance of the Whitsun Plays. Though the mayor and council were the final arbiters of whether to produce the plays, the companies apparently could petition for a performance by submitting a 'bill' to the mayor. When the decision was favourable, the companies began to ready their materials and to practise their parts.

Their first but least difficult task was to ride the Banns. The guilds participated in a yearly procession at Midsummer whenever the Whitsun Plays were not performed; consequently, they could anticipate the demand for costumes and horses for the character who rode with them and be ready to ride in procession by St George's Day, the time David Rogers claims was set aside for the Banns. If the route for the Banns was the same as that for the Midsummer Show, the companies assembled at the Bars outside Eastgate, where the crier read the Banns and called forth the guilds. The route then took them past the prisons at Northgate and at Chester Castle, where they contributed money to the prisoners (in one year the Smiths spent two pence). The liberties of the city extended beyond the walls, but by passing through the major streets and by coming to each of the gates, the guildsmen would thereby reconfirm the city's boundaries and freedoms. At then end of the day there would be a feast. On the day the Smiths spent 2d on the prisoners, they spent six shillings on their banquet, and five shillings on minstrels.

At first glance, the attitude to the plays in the later Banns indicates that they were already considered more of a tradition than a meaningful art form. In the Banns attention is drawn to the curious wagon staging, the archaic language which may not carry meaning for contemporary audiences, and the dramatic crudity of allowing God to be impersonated on stage by an actor with a gilded face. The plays are compared disadvantageously to the sophistication of the modern theatre, its actors and audiences (this was written in Elizabethan times). The spectators are asked to make allowances for the time in which the plays were written and the circumstances of their performance:

- "By craftsmen and mean men these pageants are played, and to commons and country men accustomably before".

Yet these disclaimers should not be taken too seriously. The later Banns are an attempt to defend the plays publicly against criticisms of them as theologically unsound and dramatically blasphemous. To present them as something once revolutionary which has now lost its purpose is a clever way of urging their continuation as a worthwhile but harmless local custom.

This ceremonial function concluded, the companies would begin to prepare their plays by copying and handing out parts ('parcells') from the master copy kept in the Pentice, holding trials for roles, and rehearsing from one to three times before their general rehearsal. Each rehearsal and the final performance seems in some cases to have required the purchase of sometimes copious amounts of food (beef, chicken, bread, cakes and cheese) and drink (wine and beer). The Mayor, at least in later years, saw all the plays at some point, but whether he visited each separately or saw them as a group is uncertain. Minstrels were hired for the performances and these presumably played while the carts carrying the stages were being moved from place to place, as the Painters et al paid for "a mynstrell to goe before vs". Both the mistrels and the players were treated to breakfast. The surviving account books of the guilds give a lot of detail on the expenses associated with the plays (humourously, the books relating to the Flood are too water-damaged to be clear) listing expenses for gloves, the dressing of boys, ribbons etc. One reason why the records are kept in such detail is that the guild "book-keeper", elected from year to year, was responsible for any shortfall out of his own pocket. The books perhaps also show how the plays provided a means for distributing the subscriptions levied from the members back to them.

An antiquarian, Robert Rogers, Rector of Gawsworth and Archdeacon of Chester, included a description of the plays among his notes which passed to his son David on his death in 1595. David copied these notes in at least five versions between 1609 and 1637. The route described began at the Abbey gate outside the cathedral where, according to David's 1637 version in Liverpool University Library's Special Collections, 'the monks and Churche mighte haue the firste sight'. It then passed down Northgate Street to the High Cross in front of St Peter's Church where stood the Pentice, Chester's then "town hall" - 'Before the mayor and Aldermen', says David. The next station was somewhere in Watergate Street, and the pageants then passed through the back lanes Weaver Street and Commonhall Street to the fourth station in Bridge Street and then along Pepper Street and what is now Newgate Street to the Eastgate, the last station. Almost all of this route is downhill. Chester's plays belonged to the clergy, to the aldermen, and to all the citizens, not to an elitist group, and when the arrangements were varied in 1575 there is evidence of discontent that the plays did not tour the city as widely as usual.

Dugdale makes it clear that one of the purposes of Mystery Plays (he is writing about Coventry) was to attract visitors (and hence business) to the city:

- "I have been told by some old people who in their younger years were eye witnesses of these Pageants so acted that the yearly confluence of people to see that shew was extraordinary great and yielded no small advantage to this city."

A few companies had other, particular roles in the annual round of customs: the Butchers' and Bakers' guilds provided the bull which was baited when a new mayor took office, and the Drapers, Saddlers, and Shoemakers participated in the Shrove Tuesday festival.

Decline

During the Reformation such plays were considered ‘Popery’. The returned Genevan exile Christopher Goodman (then rector of Aldford) wrote complaining about the plays in 1572 - he felt that the plays were heretical and dogmatically Roman Catholic. Goodman begins his 10 May 1572 letter to the earl of Huntingdon, the goal of which is the destruction of the Chester Cycle, with a brief historical sketch of the Chester mystery plays:

- "certain plays were devised by a monk about 200 years past in the depth of ignorance, & by the Pope then authorized to be set forth, & by that authority placed in the city of Chester to the intent to retain that place in assured ignorance & superstition according to the Popish policy. against which plays all preachers & godly men since the time of the blessed light of the gospell have inveyed and impugned"

The plays were consequently banned by the Church of England under Elizabeth I. Despite this growing uneasyness with the plays, the cathedral paid for the stage and beer as in 1562. The performance schedule in the 1560s and 1570s was erratic - plays were performed only in 1561, 1567, 1568, 1572, and 1575 - and Henry Hardware, for example, did not allow a performance of the plays in his first mayoral term in 1559-60. The reason for not performing the plays may have also been influenced by the fact that the mayors in some of the years when the plays were not performed were members of the gentry rather than members of the guilds, and in 1574 and possibly other years, by the plague.

On 25th February 1570, Elizabeth I, daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, was excommunicated by Pope Pius V. This was done by means of a papal bull: "The Damnation and Excommunication of Elizabeth Queen of England and her Adherents, with an Addition of other punishments" - also known as Regnans in Excelsis. The Bull was issued in support of, but only arrived following, the 1569 "Northern Rebellion" in England, an unsuccessful attempt by Catholic nobles from Northern England to depose Queen Elizabeth I of England and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots (the descendant of Henry VIII's sister Margaret).

In 1572, in the mayoralty of the Protestant John Hankey, the authorities approved a production which went ahead despite the known opposition of the national authorities and of factions within the city. Various records tell us that the plays were "againste ye willes of ye Bishops of Canterbury Yorke and Chester"; that "manye of the Cittie were sore against the settinge forthe therof"; and that "an Inhibition was sent from the Archbishop to stay them but it Came too late". Chester’s major in 1574/5, Sir John Savage (gent.) who also allowed the plays (following a split vote in the Assembley), was subsequently summoned to the Star Chamber in London to explain himself. The 1575 wording in the Mayor's book concerning this is quite delightful:

- "Sir John Savage caused the popish plays of Chester to be played the Sunday Monday Tuesday and Wednesday after Midsummer day in contempt of an inhibition and the Primate's letters from York and from the Earl of Huntingdon. For which cause he was served by a pursuivant from York the same day that the new mayor was elected as they came out of the common hall notwithstanding the said Sir John Savage took his journey towards London but how his matter sped is not known. Also Mr Hankey was served by the same pursuivant for the like contempt he was mayor. Divers others of the citizens and players were troubled for the same matter "

The plays certainly did not go down well with everyone. In 1575 Andrew Tailer, a member of the Dyer's company refused to pay his subscription (3s 8d) towards the funding of the plays and was thrown into prison as a result. He was not released until Henry Hardware became mayor in October 1575 and two of his supporters paid his subscription for him.

Savage wrote to the city council to request a certificate that the council and not he alone had ordered the plays, and Henry Hardware (Draper), who was mayor 1575/6, was honourable enough to send the certificate stating that both Savage and Hankey (Merchant and Vinter, mayor 1571/2) had acted with the consent of the Assembley. Apparently, this shared 'guilt' satisfied the government, or the city's charter prevented any further action against the two past mayors. Nevertheless, the message was clear and the plays were never performed in Chester again after 1575, except for one performance of the Shepherds before the Lord Strange and other notables in 1577-8. Perhaps this final ban was encouraged by the "Marian" elements found in the plays and the concurrent focus of rebellion around Mary, Queen of Scots - at that time imprisoned but still alive. Also at this time Elizabeth had begun to establish her cult of virginity - in 1559 she told the Commons, "And, in the end, this shall be for me sufficient, that a marble stone shall declare that a queen, having reigned such a time, lived and died a virgin". Perhaps the presence of a second Mary and a second Virgin in the play were simply too much.

Even after the plays had been effectively banned the same people were involved in political and religious cotroversey. A list, compiled in c1579-80, of county leaderssuspected of recusant leanings includes major figures such as William Brereton of Brereton and his father-in-law, Sir John Savage. Savage had sent his son abroad to be educated, which was usually taken as a sign of Catholic sympathy. A document at Hatfield House, a report to Lord Burleigh, shows that the Earl of Derby, then Lord Lieutenant of Cheshire, was suspected of wishing to abet the escape of Mary Queen of Scots. Although the career of neither man suffered as a result of these suspicions, the national authorities were keeping a close watch on those in local positions of responsibility and, in an area where recusancy was a potential threat, incautious acts such as the promotion of 'popish plays' would attract considerable attention. The Earl was alleged by Goodman to have given Hanky some support in his wish to have the Plays performed in 1572, while it was in Savage's mayoralty, in 1575, that the Plays were performed for the last time.

Revival

The 1818 edition by James Heywood Markland, himself educated at Chester, of two plays from the Chester cycle represented the first modern edition of any English mystery plays. It was followed by improved editions of the full cycle, each in two volumes, published in 1843–7 and 1892–1916. Prior to this, the plays were often described (for example by Thomas Warton) as buffoonery and for many years the prevailing view was that there was no serious English theatre before the age of Shakespeare. Warton appears to have had hardly and access to the texts of the Mystery Plays and to have based his conclusions on the preface of Robert Dodsley's "Selected Old Plays". This view changed in the later 19th century.

A new interest in the performance of medieval plays was stimulated by William Poel's production of Everyman at the Charterhouse in London in 1901; it was paired with a production of Chester's Sacrifice of Isaac, the first performance of a Chester play in modern times. One of Poel's company, Walter Nugent Monck, formed his own company and staged versions of Chester's Nativity, Shepherds, and Magi plays in Bloomsbury Hall, London, in 1906. Monck wrote to the Chester Archaeological Society offering to produce the whole cycle in the traditional manner over three days at Whitsun 1907. The proposal, which must be seen against the background of Chester's music festivals and the city's growing concern with its past, would have resulted in the first complete revival of any English play-cycle. The Society organized a public meeting chaired by the bishop to discuss it. Although the dean of Chester opposed the production, the cathedral organist, Joseph Cox Bridge, supported it, and a number of Cestrians who had seen Everyman in London or on tour reported favourably on the production. Following the meeting, the three 'Nativity' plays were performed at the Chester Music Hall on 29th November 1906 to test local reactions. An edition of the performance-text by Bridge was published to accompany the production. The production was enthusiastically received by most (as reported in the The Chester Courant and Advertiser for North Wales), although there were some objections - notably by the Dean John Lionel Darby. But the society then decided that the cost of staging the full cycle was too high and the scheme fell-though. There was also possibly competition for funding with the forthcoming "Chester Pageant" of 1910.

Christopher Ede directed the first modern revival at Chester in the Cathedral Refectory to mark the Festival of Britain in 1951. The text of the plays was compiled by Betty and Joseph McCulloch, but omitted The Fall of Lucifer, the Massacre of the Innocents, the Harrowing of Hell and the Last Judgement (Doomsday). York's play cycle was actually performed two weeks before and the Players of St Peter had been performing the plays in London roughly every five years since 1946. Further performances of the plays at Chester took place in 1952 and then 1957 (using a translation by Donald Hughes) and since then there have been productions approximately every five years. 1962 saw the use of a new translation by John Lawlor and Rosemary Ann Sisson when Ede brought the plays out into the light (and rain) of the Cathedral Green. Even in the 1950's and early 1960's there were elements of censorship as the figure of Christ was not allowed to be portrayed on stage until the summer of 1966. The 1951 York play was the subject of prolonged legal argument about the blasphemy laws and the threat of disruption by Christian evangelicals.

The text of the plays is mutable and is frequently modified to reflect current issues and provide humour relevant to the present day.

List of plays and guild associations

It is not easy to account for the number of transcripts of the Chester Plays which were made in the closing years of the sixteenth century and at the beginning of the seventeenth. Five copies made during this period are still preserved:

- The first of these was written in 1591 by Edward Gregorie a scholar of Bunbury (he was the son of a Beeston yeoman who inherited his father's library, and he turns up as warden at the radically Puritan church at Bunbury) and is now in the possession of the Duke of Devonshire;

- The two next in date now MS Additional in the Brit Mus No 10,305 and MS Harl No 2013 were written by Ironmonger George Bellin in 1592 and 1600 (Bellin was parish clerk at Holy Trinity in Watergate Street);

- The fourth was written by William Bedford in 1604 (he was clerk to the Brewers, parish clerk at St Peter's Church and also did work for the Pentice) and is now in the Bodleian Library MS Bodley No 1 75 and the latest in date.

- MS Harl No 2124 was written in 1607 by James Miller (rector of St Michael's, Chester, precentor at the Cathedral and benefactor to St. Mary's, whose will attests a considerable library including English works, chronicles and histories).

All these transcripts made by persons who were not well acquainted with the language of the original MS from which they copied or with palaeography and included errors. The biblical plays performed in Chester at the beginning of the fifteenth century probably looked different, perhaps very different, from the cycle that Gregorie, Bellin, Bedford, and Miller may have seen — which itself may have differed in important ways from the version that they wrote down.

The charter of 1208, restricted trade in the city of Chester to the "..men of Chester and their heirs..", formally excluding non-residents and women from mercantile activities and establishing a system of hereditary trading rights. The much coveted status of ‘freeman’, bestowed by the Guild Merchant and a necessary qualification to carry out legal trade in the city, was, therefore, restricted to this Chester-based fraternity. These restrictions continued well into the fourteenth century but, in a period pockmarked by plague and low life-expectancy, there was a dearth of suitable candidates, which necessitated a widening of the franchise. Therefore, in 1392, apprenticeships were established which, when completed, allowed outsiders to join their respective company upon payment of a fee to the Guild Merchant for inclusion in the Freemen Rolls. The guilds were social and until the Reformation religious organizations as much as economic ones, with concerns which focused on burial of the dead and camaraderie with the living. Members of the Smiths' company, for example, were fined in 1501 for failing to attend a brother's funeral. Sometimes the boundaries between different companies is hard to define exactly: Mercers and Drapers being a case in point, where there is a rough separation in that the Mercers sold costly silks, velvets, damasks, and the fine linens of Flanders and Brabant, whereas the Drapers marketed fine woollen textiles, manufactured especially in Coventry and the West Riding of Yorkshire. Other factors in the "division" between these guilds may have included geography Bridge Street as oposed to Northgate Street and parish.

The content of the plays often appears to be well-suited to the guilds associated with them. In some cases this may be because the subject-matter suggested which guild should perform the play, in others the script of the play may have been adapted to make jokes about the guild in question. However it may be that the allocation is simply the order of the Corpus Christi procession. The total cast needed for the plays seems to be about 350 people, some ten percent of the population of Chester at the time. In York the guilds were also perhaps allocated to the plays by profession: for example, the Shipwrights performed the Building of the Ark, while the Butchers played the Death of Christ or Crucifixion. The Chester alignment of guilds with particular plays seems clearer than that at York, but different sources may give slightly different associations between the plays and guilds. This latter variation may be due to the membership of guilds relating to multiple trades changing over time.

The size of individual guilds before 1500 is difficult to determine. Nineteen men witnessed the Fletchers and Bowyers' charter in 1468, and in the 1490s both the Bakers and the Butchers had a membership of c. 18. About 1576 the Cappers and Dyers had 6 members each, the Saddlers, Fishmongers, and Goldsmiths 9, the Skinners 10, the Barbers and Mercers 15 each, the Fletchers and Weavers 19 each, the Joiners 21, the Butchers 23, the Drapers 26, and the Smiths 33.

Already by the 1420s some trades were collaborating with others in order to stage a Corpus Christi pageant: the Fletchers, Bowyers, and Stringers with the Coopers and Turners, for instance, and the Weavers, Walkers, and Chaloners with the Shearmen. Sharing of costs continued later: in 1521 the Smiths agreed with the Founders and Pewterers to continue their joint contributions. Some of the pageant groupings resulted in the formation of guilds which combined men following disparate trades, but others were simply ad hoc, if long-lasting, arrangements between what always remained separate companies. The Masons and Goldsmiths, for example, put on a pageant together by the 1430s but were distinct guilds, as were the Cappers and Mercers c. 1520. Some crafts which were either wholly new or newly prominent after the mid 15th century never formed a guild of their own: makers of felt caps were part of the Skinners' company by 1489, and glaziers belonged to the Painters' company by 1482. Changes in the arrangements of the pageants between c. 1500 and the Reformation may have precipitated a further restructuring of certain guilds. Three guilds (the Tanners; the Cappers and Pinners; and the Painters, Glaziers, Embroiderers, and Stationers) put on their own pageants for the first time. Conversely the Cooks' guild merged with that of the Tapsters and Hostellers to put on a single play, and the Ironmongers similarly collaborated with the Fletchers and Coopers. The last arrangement, however, did not lead to permanent union in a single guild, perhaps because at the Reformation they separated again in order to replace the pageant previously put on by the Worshipful Wives.

The notes on the plays given below quote the post-Reformation "Banns" which in some cases attempt to explain away some of the non-biblical references in the plays and identify the guilds involved. These Banns are a unique feature of the Chester plays and can be seen as advertising for the forthcoming plays. It also notes the guild allocation of the corresponding York plays. Finally a few notes are included on elements which a young William Shakespeare may had recalled from the plays in Coventry, which is likely to have seen as a boy, and later included in his own works.

First Day

1 - The Fall of Lucifer (Barkers and Tanners)

York also has a single play for this subject: Barkers (Tanners) – The creation, and the Fall of Lucifer

- "Now, you worshipful Tanners, that of custom old, The Fall of Lucifer did truly set out! Some writers a warrant your matter; therefore be bold lustily to play the same to all the rout. And if any therefore stand in any doubt your author his author hath. Your show let be! Good speech, fine players, with apparel comely!"

In some cities Barkers have been claimed to be a guild of those who attempted to attract patrons to entertainment events, such as a circus or funfair, by exhorting passing public (this may well be an error on the part of modern guild members). This was not the case in Chester: here Barkers collected oak bark for the Tanners, who worked in exceedingly noxious conditions in the Tanning trade: perhaps they got the play for that reason or perhaps as they were particularly important guilds had the priviledge of going first. The first Pageant, that of the Fall of Lucifer, tells the story in the traditional manner - which elaborates on the very sparse biblical version (if there is a biblical version at all). Lucifer, the greatest and fairest of the angels, falls because during God's absence, after having sworn fealty, he sets him-self up for worship. Certain of the angels acknowledge his claim - God returns and slings him out. One curious feature is that after their fall the fallen angels are not alluded to by name but are called Primus and Secundus Demon.

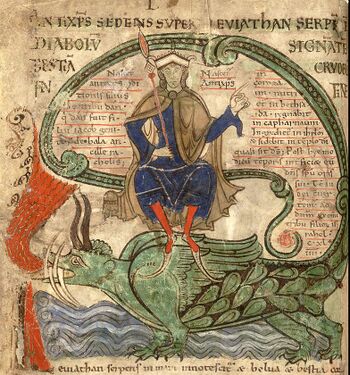

Lucifer is a Latin name for the planet Venus in its morning appearances, and is often used for mythological and religious figures associated with the planet. Due to the unique movements and discontinuous appearances of Venus in the sky, mythology surrounding these figures often involved a fall from the heavens to earth or the underworld. The Sumerian goddess Inanna (Babylonian Ishtar) is associated with the planet Venus, and Inanna's actions in several of her myths, including Inanna and Shukaletuda and Inanna's Descent into the Underworld appear to parallel the motion of Venus as it progresses through its synodic cycle. The fall from heaven motif also has a parallel in Canaanite mythology. In ancient Canaanite religion, the morning star is personified as the god Attar (another corruption of Ishtar, cf Astarte, Astaroth, who attempted to occupy the throne of Ba'al and, finding he was unable to do so, descended and ruled the underworld. Attar is frequently depicted as an ibex, often mistaken for a goat. The French equivalents of this mystery play have Lucifer, Astaroth and Satan as separate "demons".

Typical depictions of Lucifer provide bat-like, leathery wings and horns. Another possible origin for the "horned devil" is the Gaulish Celt deity Cernunnos (the Horned One) the etymology of Cernunnos is unclear, but seems to be rooted in the Celtic word for "horn" or "antler". Cernunnos may have been assimilated into christianity in both a negative sense (as the devil) and a more positive sense as the stag or deer as an integral part of myths, legends and fables - such as the foundation legend of St Johns in Chester. Barkers collected oak bark (and brought it into Chester down Barker's Lane, and had an association with the "Green Man". It has frequently been suggested that the Christian Devil is simply a negative reference to a collection of previous deities.

It is not clear whether the entire host of angels mentioned would be walking in procession with the wagons (there would be no space for all of them on the wagons). The Banns make it clear that this version might not suit everyone: "if any therefore stand in any doubt your author his author hath" - in other words, we are simply performing the version handed down from the distant past.

2 - The Creation of the World (Drapers and Hosiers)

York next has six plays: Plasterers – The creation – to the Fifth Day; Cardmakers – Creation of Adam and Eve; Fullers (preparers of woollen cloth) – Adam and Eve in Eden; Coopers (makers of wooden casks) – Fall of Man; Armourers – Expulsion from Eden; and Glovers – Sacrifice of Cain and Abel. Chester conflates these into one.

- "Of the Drapers you, the wealthy company, The Creation of the World! Adam and Eve according to your wealth, set out wealthily, and how Cain his brother Abel his life did bereave."

Drapers and hosiers may have been assigned to this play because of the lack of clothing of Adam and Eve initially. In the alternative the Drapers may have used large sheets of cloth to illustrate the creation of the world, including a "Mappa Mundi". The drapers were wealthy men and over the period 1380-1509 provided 17 sheriffs and 9 mayors, their power being especially marked after 1460. They may have clustered in Northgate Street, where they apparently sold cloth from their own shops. Between 1500 and the end of Chester plays in 1575 they produced 23 mayors of Chester - almost one third.

These plays are continuous; one merges into the other. The pageants must have followed one another quickly through the streets, one taking up the story very nearly where the other leaves it. Cestrian David Rogers is especially impressed by the way that the plays seem to push in on each other, so that no play ends without the next one being visible:

- "the weareplayed upon mondaye tuesedaye and wensedaye in whitson weekeand thei firste beganne at the Abbaye gates. and when the firstepagiante was played at the Abbaye gates then it was wheled from thense to pentice at the hyghe crosse. before the maiorand before that was donne the seconde came. and the firste wenteinto the watergate streete. & from thense unto the Bridgestreeteand so one after an other tell all the pagiantes weare playedappoynted for the firste daye. and so likewise for the seconde and the thirde daye. these pagiantes or cariage was a higheplace made like a howse with 2 rowmes beinge open on thetope. the lower rowme their apparrelled and dressed them selues. and the bigger rowme[s] theie played. and thei stoode upon vi wheeles. and when the had donne with one cariage in one place theie wheled the same from one streete to another. firste from the Abbaye gate. to the pentice. then to the watergate streete. then to the bridge streete. through the lanes &so to the esttgatestreete. And thus the came from one streete to another. kepinge a diverse order in everye streete for before thei firste Carige was gone from one place the seconde came and so before the seconde was gone the thirde came and so till the laste was donne all in order withoute anye stayeinge in any place. forworde being brougthe howe everye place was neere doone the came and make noeplace to tarye tell the laste was played."

However, there is an immediate problem. This second play is twice the length of the first, and so even if it started playing at the Abbey Gateway as soon as the first play finished it could not be expected to arrive at the second station (the High Cross) at the close of the performance of the earlier play. Worse still, the following play is the length of the first and so would arrive before this play was completed.

The second play tells the story of the six days of Genesis. Adam and Eve, according to the creation myth of the Abrahamic religions, were the first man and woman. They are central to the belief that humanity is in essence a single family, with everyone descended from a single pair of original ancestors. It also provides the basis for the doctrines of the fall of man and original sin that are important beliefs in Christianity, although not held in Judaism or Islam. Adam is created, but until after the sleep in which Eve is formed from his rib, he does not speak a word. The word "rib" is a pun in Sumerian (which also has a version of this myth), as the word "ti" means both "rib" and "life". There are other puns in the creation myth: the words meaning "naked" and "knowledgable" also sound very similar.

From the stage directions we gather that Adam rises when he is told to do so, but it is not until after his sleep that he has any words to utter.

This play also contains the story of Cain and Abel. In some modern versions of the play this is performed separately as is also the case with some other mystery play cycles. Play 2 deals with the creation of man and with the beginnings of sin among mankind. Man's first and "original" sin is the wilful disobedience of God's known will, mythologised as the eating of the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. For this man is denied eternal life and is expelled from Eden into a harsh world. Within this world in the play the consequences of that sin are enacted in Cain's fratricide of Abel, Man's sin against God beging paralleled by his sin against his fellow Man. The two are linked in Eve's self-recrimination when Cain returns to his parents before going into exile. It has been proposed that the etymology of Cain and Abel may be a direct pun on the roles they take in the Genesis narrative. Abel is thought to derive from a reconstructed word meaning "herdsman", with the modern Arabic cognate ibil now specifically referring only to "camels". Cain is thought to be cognate to the mid-1st millennium BC South Arabian word qyn, meaning "metalsmith". This theory would make the names descriptive of their roles, where Abel works with livestock, and Cain with agriculture—and would parallel the names Adam ("man," אדם) and Eve ("life-giver," חוה Chavah).

3 - Noah and his Ship (Waterleaders and Drawers in the Dee - Helped by the Brewers)

York next has two plays: Shipwrights – Building of the Ark and Fishers and Mariners – Noah and his Wife. Chester combines these into one:

- "The good, simple Waterleaders and Drawers of Dee, see that in all points your Ark be prepared.Of Noah and his Children the Whole Story: and of the Universal Flood, by you shall be played"

These "guilds" (it is not clear that they had full guild status) were obviously chosen because of their association with the River - Waterleaders were responsible for bringing water to the citizens of Chester from the River Dee and Drawers of Dee were fishermen. At about the time of their incorporation (1607), the beer brewers combined with the water leaders and drawers of Dee in the Midsummer Show; in 1607 the beer brewers also paid 13s 6d for taffeta for a banner for the company’s use at Midsummer and 40s to Randle Holme, the heraldic painter, for painting it. The association with the brewers is apt because Noah's wife prefers to drink with her friends rather than get abord the ark and Noah is also known for his boozing.

The Noah story of the Pentateuch is almost identical to a flood story contained in the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, composed about 2000 BC. In the Gilgamesh version, the Mesopotamian gods are enraged by the noise that man has raised from the earth. To quiet them they decide to send a great flood to silence mankind. Various correlations between the stories of Noah and Gilgamesh (the flood, the construction of the ark, the salvation of animals, and the release of birds following the flood) have led to this story being seen as the inspiration for the story of Noah.

This was perhaps the favourite play of all. It gave opportunity for the kind of horse-play, especially marital, which the people of the middle ages so much loved. When the ark is built Noah's wife has changed her mind and will not enter it, and then the fun starts. Noah tells her to go into the ark but she refuses and the play turns to slapstick comedy with Noah's wife complaining about ferrets and stoats. Of the five extant middle English Noah plays, the Chester cycle’s Noah’s Flood is the only one that attempts to represent the actual loading of the beasts and birds onto the ark. All five manuscripts of the Chester play agree in their emphasis on this critical moment of the deluge story, naming up to forty-seven different creatures in a verbal catalogue parcelled out to seven of the main characters.

The dispute between Noah and his wife is only found in the Towneley and Chester Plays, but probably it was one of these to which Chaucer alludes in the Miller's Tale, where he speaks of: "The sorwe of Noe with his felawship / Or that he mighte get his wif to ship". Chaucer wrote in the 1380s–1390s and is known to have visited Chester having taken part in the "Scrope" trial at St Johns. Millers in Chester were generally regarded as crooked - taking more than their allocated share of what they ground. Chaucer's next tale, The Reeve's Tale, has a crooked miller who steals wheat and meal brought to him for grinding.

The lists of animals given by the various characters appears to be symbolic and the stage directions make it clear that it should not be tampered with. Shem leads off with heraldic beasts (lions and leopards representing the king and the aristocracy) then lists the horse and the ox (of little use for breeding given that oxen are castrated) followed by other domestic beasts. The inclusion of swine in this catalogue (clearly there for food-value) again shows the unimportance of biblical literalism, since an old testament culinary context would have prohibited pork as unclean — yet it appears here because it was a staple of medieval and early modern diets. Ham brings in animals which are used for work but not eaten by the public at large, as well as semi-domestic "wild" animals. Japhet gets the cats and dogs as well as small quadrupeds which were not considered edible and in many cases considered as pests: the otter, the fox, the fulmart (pole-cat), and the hare. The animals that they mention are associated with traditionally masculine activities, namely political governance (with the lion and leopard), plowing, crop production, large animal husbandry, trade (of animal commodities, such as wool), and hunting. Medieval and early modern people would have viewed these activities as comprising the backbone of their economy and the basis of its major social divisions, with the contributions of royalty, aristocracy, the mercantile class, and the peasantry clearly accounted for in the animals on the ark.

The women’s bird catalogues, generally speaking, focus on birds associated with two of women’s "traditional" activities, cooking and cleaning. Ham’s wife begins the bird catalogue with herons, cranes, bitterns, swans, and peacocks, all birds that were eaten at aristocratic banquets. The play, as scholars and critics have noted, focuses on issues of labour: how to organize necessary tasks, how to complete tasks expeditiously, and how to parcel out duties so that all members of the household share the labour. As David Mills writes, "the image of organized labour, each [character] with an appropriate task to perform, is in contrast to the more individual and comic construction of the ark in York or Towneley". Noah’s wife violates a number of principles that inform the catalogues of the other characters: not a single one of her animals contributes to the household economy. None is edible and none performs worthwhile labour. They are either entertaining animals or useless predators with bad reputations, let loose on the ark without any clear way to control them. Given Noah’s wife’s reluctance to work in the earlier scene — her excuse being that women are too weak to perform great labour — her animals continue this theme of idleness. By the mid-sixteenth century, protestant disapproval of bear-baiting was evident, and Chester’s puritan mayor actually banned bear-baiting in Chester in 1599–1600 — so Noah’s wife would have been going against the contemporary moralists by wanting the bear on the ark for its entertainment value. Many medieval and early modern sources suggest the foolishness of Noah’s wife’s animals.

In medieval ethnography, the world was believed to have been divided into three large-scale racial groupings, corresponding to the three classical continents: the Semitic peoples of Asia, the Hamitic peoples of Africa and the Japhetic peoples of Europe. It is not clear therfore why Japhet should get the "dregs".

The Noah's Flood play was set operatically by both Benjamin Britten (Noye's Fludde) and Igor Stravinsky (The Flood).

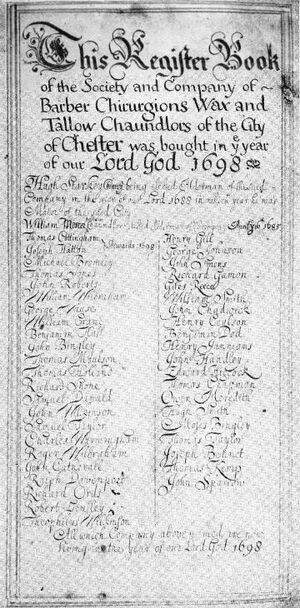

4 - Abraham and Isaac (Barber Surgeons and Wax-chandlers)

York has a single play next: Parchmenters and Bookbinders – Abraham and Isaac. Chester also has one:

- "The Sacrifice that Faithful Abraham of his Son should Make, you Barbers and Wax-chandlers of ancient time in the fourth pageant with pains ye did take. In decent sort set outt he story is fine. The offering of Melchysedeck of bread and wine and the preservation thereof set in your play. Suffer you not in any point the story to decay."

The Barber surgeons were possibly selected for this play because God instructs Abraham to circumcise his son, Isaac. This Company combined the crafts of medicine, hair trimming and candle making. There is little reason for this association which may have only come into existence to make up numbers required for the performance of the play. It is known to have been in existence by 1475 and received charters from Chester Corporation in 1540 and 1550. The verses recording the Sacrifice of Isaac are among some of the best in the whole of the plays. The broken-hearted father doing what he conceives to be the will of God and the son obedient unto death. As in the traditional story Isaac is saved by his substitution by a 'Ram in a Thicket'. This also seems to be related to ancient symbolism - the Ram in a Thicket is a pair of figures excavated in Ur, in southern Iraq, and which date from about 2600–2400 BC. One is currently exhibited in the Mesopotamia Gallery in Room 56 in the British Museum in London; the other is in the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, USA. The pair of rams would more correctly be described as goats, and were discovered lying close together in the 'Great Death Pit', one of the graves in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, by archaeologist Leonard Woolley during his 1928–9 season.

Rule 18 in the Barber-Surgeons books provides for their appearance in the Midummer Watch:

- "It is further ordered and agreed upon by the said company that upon every Midsome even at the Watch at the companys charge the Stewards for the time being are to provide against that time & times one to ride Abraham and a young stripling or boy to ride Isaac and they to be set forth according to the ancient custom as hath been before times used in the company and the said Stewards for the time being to do their best in the setting forth of the said Show for the better credit of the said Society and company in payn of 6s. 8d."

Thomas Hughes writes of them:

- "Chester barbers were prominent citizens, ranking with, and exercising most of the functions of, surgeons and physicians. They dressed wounds, drew teeth, bled their patients in more ways than one, made up ointments and pills calculated either to kill or cure in all sorts of disorders as were to be found anywhere within our ancient walls. Excellent artificers in the making of wigs and perukes, they earned full many an honest penny in the plaiting and adornment of pigtails — another of the vanities affected by our grandsires."

The "Brome play of Abraham and Isaac (also known as The Brome “Abraham and Isaac”, The Brome Abraham, and The Sacrifice of Isaac) is a 15th Century play of unknown authorship, written in an East Anglian dialect of Middle English, which dramatizes the story of the binding of Isaac. The text of the play was lost until the 19th century, when a manuscript was found in a Commonplace Book dating from around 1470–80 at Brome Manor (demolished 1958), Suffolk, England – thus, the name of the play. The manuscript itself has been dated at 1454 at the earliest. This manuscript is now housed at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. The Brome Abraham’s relation to the play of the same subject in the cycle of Chester Mystery Plays has attracted attention. A comparison of the texts reveals around 200 lines of striking similarity, in particular during the debates between Abraham and Isaac that are at the hearts of the plays. It is not difficult to see why Shakespeare would have had the Abraham and Isaac story in mind while dramatizing Hubert’s reluctant efforts to cany out King John’s orders to blind young Arthur (the adopted son of Ranulf de Blondeville, Earl of Chester). The strange mixture of childish terror and quiet obedience which is found most strikingly in Chester and Brome is certainly there in Shakespeare. But Shakespeare could not have seen this in Coventry - since the 1530s it had consisted of only ten pageants covering exclusively New Testament material from the Annunciation to Doomsday.

5 - Balak and Balaam (Cappers, Wiredrawers and Pinners)

York follows with: Hosiers – Departure of the Israelites from Egypt;Ten Plagues; Crossing the Red Sea: Chester has a unique play:

- "Cappers and Linendrapers, see that ye forth bring in welldecked order That Worthy Story of Balaam and his Ass and of Balaack the King. Make the ass to speak, and set it out lively"

This is unique in the Chester Plays; it does not occur in any of the other English cycles, though it is to be found in the French mysteries - some passages in this play are almost exact translations from the French. Some versions of the plays omit this story completely. Balaam, the non-Jewish sorcerer and prophet was commissioned by Balak King of Moab to curse the Jews, found himself incapable of cursing them. It is in this play that we have the first mention of "Mohammed" (in the original text). The story relates how Balaam was blocked from progress (on his donkey) ...

- ..in a path of the vineyards, with a wall on both sides. The donkey saw the angel, and she pressed against the wall (to squeeze past the angel), crushing Balaam's "leg" and destroying his "tools", and he beat her again. Then the angel stood in a narrow place, where there was no room to turn right or left..

This looks like a clear reference to wire-drawers, but the wire-drawers were possibly at the time associated with the guild of "Smyths, Cutlers, Pewterers, ffounders, Cardmakers, Girdlers, Headmakers, Wiredrawers, & Spurriers".

The original story is quite bawdy, with the donkey able to talk. The Talmud also suggests that Balaam has had sex with the donkey, as the donkey says:

- ..Since you first started until now you have always ridden on me. Moreover by day I provide you with riding, and by night with intimacy.. (Rashi, Numbers 22:30; Avodah Zarah 4b.)

The rude mechanicals of Shakespeare's "A Midsummer Night’s Dream" may be a comic rendition of the artisan actors of the provincial mystery plays, including the talking ass of Balaam.

According to the guild website, the cappers made firing caps for guns. This is untrue, the percussion cap only replaced the flint, the steel "frizzen", and the powder pan of the flint-lock mechanism following its invention by Joseph Egg, around 1817. "Cappers" is probably better translated as a maker of headgear (from Old English cæppe, from Late Latin cappa). As the play required the manufacture of a donkey head for one of the cast to wear, it was appropriate that it should go to the cappers.

The Cappers Company was in existence by 1523-24, when it petitioned the Mayor and Aldermen, complaining that, because of competition, mainly from the mercers, it was too impoverished to produce its play. Perhaps because of this, the Cappers were joined by the Pinners and Wierdrawers in producing ‘King Balak and Baalam with Moses’, probably by c.1540. By 1603, the Linen Drapers had amalgamated with the Cappers, Pinners and "Wierdrawers".

In 1967, at Deir Alla, Jordan, Dutch archaeologists found an inscription with a story relating visions of the seer of the gods Bala'am, son of Be'or, who may be the same Bala'am mentioned in Numbers 22–24. This Bala'am differs from the one in Numbers in that rather than being a prophet of Yahweh he is associated with Ashtar, a god named Shgr, and Shadday gods and goddesses. The inscription is datable to ca. 840–760 BCE. The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies describes it as "the oldest example of a book in a West Semitic language written with the alphabet, and the oldest piece of Aramaic literature."

6 - The Nativity (Wheelrights, Slaters, Tylers, Daubers and Thatchers)

York next has three plays: Spicers – Annunciation and Visitation; Pewterers and Founders – Joseph's trouble about Mary; and Tile-thatchers – Journey to Bethlehem & the Nativity of Jesus. Chester has one:

- "Of Octavian the Emperor, that could not well allow the prophecy of ancient Sibyl the sage, ye Wrights and Slaters with good players in show lustily bring forth your welldecked carriage. The Birth of Christ shall all see in that stage. If the Scriptures awarrant not of the midwives' report the author telleth his author; then take it in sport"

Thatchers being associated with stables, this is an appropriate choice for these trades. But it might also be that some clever manipulation of the props might be needed for the "scene shifts" in this play.

The version of the nativity is different from the one in the bible as it features a walk-on part by the Roman emperor Octavian/Augustus. The play moves from Joseph's house at Nazareth to the Emperor's court at Rome, partly to show why Octavian ordered the general tax but more importantly to evaluate the pax Romana into which the Prince of Peace was born. The Roman senate believe that the long peace and prosperity of Octavian's rule must be a sign of his divinity and request his deification, but Octavian recognises his own mortality and rejects the offer. He then consults a sibyl who foretells the birth of a child of greater power than he. The action returns to Bethlehem for the birth, but then reverts to Rome, where Octavian is granted a vision of the Virgin and Child in a star and orders his countrymen to worship the Child. In the course of the play the pax Romana is shown to have been based upon a primitive kind of early warning system, the Temple of Peace, "contrived by a fiend", so that Rome always had advance notice of rebellion. According to one version: "at Christ's birth, the structure collapsed, and subsequently a church has been built to commemorate the vision".

The local connection is that the "church" is Santa Maria in Ara Coeli which is known for housing relics belonging to Saint Helena, mother of Emperor Constantine. In Great Britain, a later legend, mentioned by Henry of Huntingdon but made popular by Geoffrey of Monmouth, claimed that Helena was a daughter of the King of Britain, Cole of Colchester, who allied with Constantius to avoid more war between the Britons and Rome. All of this is entirely without any historical foundation. In the play the church has its name mangled: "The churche is called Saynte Marie - The sirname in a Racali". For further discussion see: Elen of the Hosts.

The myth may arise from the similarly named Welsh princess Saint Elen (alleged to have married Magnus Maximus and to have borne a son named Constantine). The church actually stands on the site of the Temple of Juno Moneta (where coins were minted). The original structure cannot possibly date back to the time of Augustus (Rome did not become officially Christian until the 4th century), but by the 6th century the existing church was already considered old. It was later rebuilt, with the present structure dating from the 13th century. There was a Temple of Peace in Rome, but this was not built until 71 AD under Emperor Vespasian. The funds to create this grand monument were acquired through Vespasian's sacking of Jerusalem during the Jewish-Roman Wars. The interior and surrounding buildings were decorated with the treasures collected there by the Roman army.

There is a curious reference to the "high horse beside Boughton" in only one version of the play (Harl Ms. 2124) which may be a grim reference to Gallows-Hill at Boughton or a reference to a local brothel in Love Street. Ulpian Fulwell in his "Like will to Like" calls the gallows a two legged mare: "This peece of land whereto you iuheritours are / Is called the land of the two legged mare / In this peece of ground there is a mare in deed / Which is the quickest mare in England for speede."

Arrived at Bethlehem, Joseph goes out to search for two midwives. He finds two, by name Lebell and Salome. The story of the birth, of Salome's disbelief of Mary's virginity, of the withering of her hand and of its healing follow the apocryphal Gospel of James (ch. XIV):

- 14 And the midwife went out from the cave, and Salome met her. 15 And the midwife said to her, "Salome, Salome, I will tell you a most surprising thing, which I saw. 16 A virgin has brought forth, which is a thing contrary to nature." 17 To which Salome replied, "As the Lord my God lives, unless I receive particular proof of this matter, I will not believe that a virgin has brought forth."

- 18 Then Salome went in, and the midwife said, "Mary, show yourself, for a great controversy has arisen about you." 19 And Salome tested her with her finger. 20 But her hand was withered, and she groaned bitterly, 21 and said, "Woe to me, because of my iniquity! For I have tempted the living God, and my hand is ready to drop off

The story of the withered hand, which may be intended as grim comedy, does not turn up in the bible, and the Banns comment upon it to excuse its presence.

7 - The Shepherds (Painters, Glaziers, (Stationers) and Embroiderers)

York then has: Chandlers (Candlemakers) – The Annunciation to the shepherds, the Adoration of the Shepherds. Chester also has a single play:

- "The appearing Angel and Star upon Christ's birth, The Shepherds, poor, of base and low degree, you Painters and Glaziers, deck out with all mirth and see that "Gloria in Excelsis" be sung merrily. Few words in the pageant make mirth truly, for all that the author had to stand upon was "Glory to God on high, and peace on Earth to Man."

The Banns evidently seek to excuse the meetting of the shepherds and their feasting and wrestling which precede the appearance of the angels and constitute a different kind of "comedy" from the angelic song - which, according to the Banns, was all the writer had to base the text of "The Shepherds" upon. These four crafts developed in the early 16th century. The painters were heraldic painters: the glaziers catered for the growing use of glass; the embroiderers embellished materials and the stationers were concerned with bookbinding and book selling. In 1534, members of these crafts successfully petitioned the Mayor, Aldermen and Common Council for a charter of incorporation. In their petition, they cited their long association with the production of ‘The Shepherd’s Offering’ in the Chester cycle of Mystery Plays. It would appear that the Glaziers included stilts in their performance.

The Adoration of the Shepherds, is one of the most important in the whole cycle, because it is of all the plays the one in which local traditions, customs and ideas receive the freest expression. It would also have been one of the more difficult to play, not only because of the lines which needed to be learned but also because of the physical acting in the "wrestling" match. The first Shepherd enumerates the various diseases to which sheep are liable and the remedies to be applied. There is then a discussion of food which mentions many things which can be supposed to be local dishes. As a playable piece of drama, to be repeated at four wagon stations, the scene is a prop master‘s nightmare.Within less than fifty lines, the three Shepherds unpack and eat "bredd", "onyons", "garlycke", "leekes", "butter", "greene cheese", "puddinge", "jannock" (a leavened oatcake), "sheepes head sowsed in ale", "grayne" (either a pig‘s snout or its groin), "sowre milke" (curds), "pigges foote from puddinges purye", "gambonns" (gammon joints), another "puddinge" (with a pricke in the end, provocatively), and "tonge". Tudd refers vaguely, three more times, to other "meate" that he has brought. Then the Shepherds drink ale ‖and other "lickour" from a "flackett", "bottell", and "bowles". In later lines, the Shepherds and their boy Trowle gesture to further items that must be visible on-stage, though they haven‘t been mentioned aloud yet: a pot for more drinking, a "loyne" (with punning reference to Hannkeynn‘s own loins), "sose" (sauce, possibly, or just a sloppy mess of food), and pickled pig parts, usually the feet and ears. The records of monies spent on the plays indicate that the Painters actually bought real food for this scene. It has been suggested that the Painters shared the food with the audience, but they do not seem (from their records) to have bought enough for that. There are some specific references to "local" dishes: one Shepherd says:

- "And brave ale of Halton I have / And what meat I had to my hire / A pudding may no man deprave / And a jannock of Lancaster-shire."

The "ale of Halton" may be a reference to Norton Priory, closed down in October 1536. In a book called "Industrial Lancashire" published in 1897, John Mortimer explains that "Jannock" was a kind of oatmeal bread introduced by Flemish weavers who moved to Lancashire from the 13th century onwards (not that different to "Bannock"). This bread was considered to be "good and wholesome" and so the word was applied to other things that were good and wholesome.

As in much medieval art Joseph is represented as an old and decrepit man, and such we find him all through these plays. The object being to emphasize the fact that he was not the father of Mary's child. The Shepherds play was one of those which Christopher Goodman found offensive to good Protestant morals - in their part of the Nativity they present humble gifts: a bell, a spoon, a cap and (from Trowle) "a pair of my wife's old hose". Four hithertoo silent shepherd boys then present equally commonplace offerings, a bottle, a hood/cape, a pipe (as in musical instrument, possibly a Pibgorn) and a nut-hook (Shakespeare uses "nut-hook" twice: in Merry Wives of Windsor Act I scene I and in Henry IV Part 2 Act V scene IV). It is not clear whether the reference to a "nut-hook" is a reference to a bishop's crosier. Strangely, the Townley cycles has gifts of a spruce coffer, a ball and a bottle and German and French plays of similar times have equally homely gifts. Edmund Spencer's The Shepheardes Calender iilustrates how pastorals were seen as a part of medieval literature.

8 - King Herod / Adoration of the Magi (Vintners)

York next has: Masons – Coming of the Three Kings to Herod. Chester also has a single play:

- "And you worthy Merchant vintners, that now have plenty of wine, amplify the story of those Wise Kings Three that through Herod's land and realm, by the star that did shine, sought the sight of the Saviour that then born should be."

Herod seems to have caught the imagination of the people of the middle ages. He appears to have been the most popular of all the characters in the mysteries. He is always represented as a swaggering, shouting braggart; this probably accounted for his popularity and possibly explains the choice of the vinters. For some inexplicable reason the characters in the original script of this play keep switching between English and French. Maybe this play was in part directed at visitors to Chester from afar, possibly having arrived via the port. One of the guilds particularly associated with the port and especially with foreign trade would have been the Vinters. Another explanation for the use of French is that it is used to illustrate how the dialog is between persons of high rank.

The portrayal of Herod was so "over-the-top" that it may have been referenced by Shakespeare in Hamlet (act 3, scene 2) where he mockingly coins the phrase "to out-Herod Herod" as an admonition to the players in the "play within the play":

- O, it offends me to the soul to hear a robustious periwig-pated fellow tear a passion to tatters, to very rags, to split the ears of the groundlings, who for the most part are capable of nothing but inexplicable dumbshows and noise: I would have such a fellow whipped for o'erdoing Termagant; it out-herods Herod: pray you, avoid it.

At one point in the text the marginal stage instructions mention a boy and a pig. This has been the subject of much puzzlement, but may be a reference to how Macrobius (c. 400 CE), one of the last pagan writers in Rome, in his book Saturnalia, wrote:

- Cum audivisset Augustus, inter pueros, quos in Syria Herodcs rex Judaeorum intra bimatum jussit interfici, filium quoque ejus occisum, ait, Melius est Herodis porcum esse quara filium Macrobii (When it was heard that, as part of the slaughter of boys up to two years old, Herod, king of the Jews, had ordered his own son to be killed, he [the Emperor Augustus] remarked, ‘It is better to be Herod’s pig [Gr. hys] than his son’ [Gr. huios]).

This has been described as a reference to how Herod, as a Jew, would not kill pigs, but had three of his sons, and many others, killed. It may be that there was originally a scene in the play where the joke about Hys/Huios was made and that this was removed for some reason, but that the stage direction was left in.

9 - The Three Kings (Mercers and Spicers)

York next has a single play: Goldsmiths – Coming of the Kings: Adoration - as does Chester:

- "And you worshipful Mercers, though costly and fine you trim up your carriage as custom ever was, yet in a stable was he born, that mighty King divine, poorly in a stable betwixt an ox and an ass"

The Spicers who later became the Grocers would have sold peper, cloves and nutmeg. This company later joined with others to form the Mercers, Ironmongers, Grocers and Apothecaries Company. These were linked by a common trade to, from or through Iberia (see: Merchant Adventurers ) The Apothecaries later left to found their own guild. At least two of the trades involved with the play (Mercers and Spicers) would been concerned with foreign trade and this play, like the previous one, takes the opportunity to portray foreign visitors in a positive light. Ironmongers are connected because Chester used to import Spanish iron. Looking at the materials used for their set (the purchase was recorded in their accounts), the Mercers covered their pageant wagon in velvet, satin, damask, taffeta, and sarsenet (a fine silk material) with green piping, materials that at once suggest the Kings‘ royalty (because of their high price) and their Eastern origins — hence, trade through the port, particularly via the Continent. Thus, the Mercers‘ had an especially commercial motive in staging their "Offerings" play — it offered them an opportunity to display their imports, which it was their business to sell. The leading mercers included some of the city's most influential men. Between 1380 and 1509 twenty-five mercers became sheriff and fifteen mayor.