Category:Religious History

This is a list of Articles in some way relating to the history of religion in and near Chester. There is a huge amount of information regarding that on the internet as for much of history the only people who wrote anything much down were various religious groups. Just don't take it all on face value - as sometimes they have a point to prove, a relic to fake etc.

Prehistory

We can only make informed guesses about what prehistoric people believed, using evidence from the monuments and artefacts that have survived. It is sometimes said that there was apparently no single or continuously developed belief system in prehistoric Britain. For long periods, however, there were religious practices concerning the dead, their afterlife, and their influence on the living. These practices have left relatively few traces, but stretch over many thousands of years.

When people began to farm the land in about 4000 BC and to settle in permanent territories, they started to place their dead in huge communal tombs. Only a small number of people were buried in this way, despite the many thousands of man hours that would have been required to build the barrows. Why these particular men, women and children were selected is unknown. Stone circles or henges appear to have developed later. There are several in the upper reaches of the River Dee. Single standing stones may include Chester's Gloverstone.

Pre-eminent amongst these burials is that connected with the Mold Cope. It's story is a remarkable mix of chance and legend. Traditionally the Roman St German of Auxerre - came to Britain in 429 and (again according to tradition) defeated the Saxons and Picts at a place known as "Maes Garmon" (which is traditionally located near Mold) in the "Battle of the Hallelujahs". The local legends included sightings of a ghostly warrior (or in some versions boy), clad in gold, a glittering apparition in the moonlight, who had apparently been reported frequently enough for travellers to avoid a local "hill" of Bryn yr Ellyllon (literally "Hill of elves" - although in some translations "ellyllon" means wraith or spirit) after dark. Workmen from a local workhouse dug into the "hill" in 1833 whilst digging for stone. They uncovered a stone lined burial chamber, within which were fragments of the crushed gold cape. Curiously, the original Welsh-language place name for Mold, "Yr Wyddgrug" was recorded as "Gythe Gruc" in a document of 1280–1281, and means "The Mound of the Tomb/Sepulchre".

From about 800 BC, in the early Iron Age, there was an even greater change. Evidence for burials is rare, but people increasingly cast valuable items – weapons, metalwork, even gold – into rivers, pools and springs, apparently as sacrifices to water gods. The area of land between Beeston Castle and Peckforton Hill to the south is marked by a number of springs and watercourses: many of these ancient springs and wells are dry today, their water usurped by a line of pumping stations at the base of the Bickerton hills owned by the Staffordshire Water Board. However, prior to the 20th century, the spring water from this area was believed to have had curative properties and was compared favourably to mineral waters from the Malverns. The spring feeding the "Horsley Bath Well" has posssibly been known since the late bronze age as the hilt and lower blade of a deliberately broken sword of that period (8th Cent BC) was found in the inner chamber of the nearby Georgian Spa building during refurbishment work in 2007 and may well have been placed there as an offering to the "spirit" of the spring.

One cannot help but note the regularity with which the story of the hunting of an animal being associated with the establishment of a church which is in turn associated with a holy spring or well turns up along the Dee. At Llangar - 'Llan Garw Gwyn' it is a (male) white deer. Upstream at Llandderfel a stag appears to have been hunted by Derfel, and downstream we have St Johns at Chester (where the well may have been "Jacobs Well"). For the ancient Celts, the white hart was a harbinger of doom, a living symbol that some taboo has been transgressed or a moral law broken - to come across a white hart was to realise that some terrible evil or judgment was imminent. The white hart's reputation improved in Arthurian legends, where its appearance was a sign to Arthur and his knights that it was time to embark on a quest - it was considered the one animal that could never be caught so it came to symbolise humanity's never-ending pursuit of knowledge and the unattainable. It was not long before Christianity managed to appropriate the white hart for its own purposes: the white stag came to symbolise Christ and his presence on earth. It has been suggested that horned animals were associated with the totems of the Cornovii and may be cognate with the Gaulish Cernunnos or the unnamed horned god of the Brigantes.

Roman

Although they famously suppressed the Druids during their invasion of Britain, the Romans were largely tolerant of other religions, provided that the conquered populace incorporated the Imperial Cult into their worship. The Romans sought to equate their own gods with those of the local population. Adherence to this ‘official’ religion demonstrated loyalty to the emperor, and was a prerequisite for social advance. But almost everybody had a private religious life. Belief in local Celtic gods persisted, and mystery cults originating in distant corners of the empire gained followers too. The persistence of pre-Roman Iron Age beliefs is seen in the significance afforded to horned gods, wet places, heads, and ritual wells and shafts. It is also evident in the occurrence of gods in groups of three, like the matres (mothers), and the three hooded deities (the genii cucullati) carved in stone at Housesteads on Hadrian’s Wall. Alongside their own gods, the Romans introduced a range of others from outside the classical pantheon. These included Mithras, an eastern god of light and rebirth, favoured by soldiers and some urban communities. His temples have been found at forts on Hadrian’s Wall, including Carrawburgh and Housesteads. There has been much speculation that Roman Chester had a Mithraeum, but no definite remains have been found.

It is not certain when Christianity was introduced to Britain, but it became increasingly popular among the elite in the 4th century after the conversion of the emperor Constantine in AD 312. Constantine appears to have come to Britain shortly after the time of the revolt of Carausius. The last known reference to Legio XX (based at Chester) is on coins struck by the usurper Carausius, and it seems likely that Legio XX joined his side in the revolt. Carausius used quotes from Vigil on his coins and Constantine would later interpret these quotes as having a religious significance: whether there is any connection is unknown.

Roman Chester's best known religious relic is the Minerva Shrine. The Minera Shrine in Edgar's Field is the only surviving rock-cut Roman shrine which is still in situ at its original location in the whole of western Europe. It dates from around AD 79, during the time of Vespasian, when the same area was being used to quarry stone for the construction of the Roman fortress (and, years later, possibly also Chester Castle) just over the River Dee. It may have been the shrine of quarry workers, or it may have been used by travelers about to cross the River Dee (by a ford) - Minerva was Goddess of both craftsmen and travelers.

Many altars have also been found including a noted one to "Jupiter Tanarus" found in Foregate Street. One other noted altar is that of Nemesis at the Amphitheatre. The eastern gateway to the Amphitheatre appears to have been significantly altered in the post-Roman period, with the large stones lining the entrance being inserted at that time. The surface of these stone is keyed as if to carry a coat of plaster. The stones which form staircases to either side are very worn indicating that they were much used. It has been suggested that the gateway was remodeled as a crypt for St Johns which may have contained relics of some kind and the wear and tear on the steps is due to the feet of pilgrims visiting the crypt. Wilfid, who has associations with St Johns, built a similar crypt at Hexham.

By Roman law, the dead were buried outside the fortress in cemeteries along the incoming roads to the north and east. Some were cremated and buried in urns, others buried in stone-lined tombs. Elaborate monuments lined the roads. Sometime in the later Roman period, these monuments were broken up and used to repair the fortress walls. During the 19th century, these tombstones were recovered from the north wall and now form the best collection of Roman tombstones in the UK. They can now be seen in the Grosvenor Museum.

Dark Ages

The conquest of much of England by the Anglo-Saxons and Viking's saw an eclipse of christianity, although it survived quite well in Wales. Archaeological evidence demonstrates a large and violent conflict took place at or near Heronbridge, just to the south of Chester. Notably, the Battle of Chester is also associated with the "massacre" of the monks of Bangor-on-Dee which potentially introduces a unique element of religious conflict during these troubled times. Bede would make much of the loss of the monks being as a result of the disharmony between the Celtic church and the church of Rome, but in reality it seems that the raid by the pagan Northumbrian Angles which led to it had little to do with religion.

Tradition ascribes the foundation of St Johns to Æthelred, king of Mercia (674–704), in 689. The direct authority for this statement quoted by John Leland is the Itinerary of Giraldus Cambrensisc (Gerald of Wales). However no such information is found in the surviving texts of the Itinerary (it was written in 1191). Two authorities of a subsequent date quote the early date in such a mannner as to imply their acceptance of it, and the source as being Giraldus. It is unclear whether the story of the foundation is based on a myth or lost work by Giraldus.

The establishment of the cult of Werburgh at Chester was a key element in the development of the city towards the end of the Dark Ages. Werburgh never visited Chester and her relics and cult only arrived in the city long after her death. Werburgh was born at Stone (now in Staffordshire), and was the daughter of King Wulfhere of Mercia (himself the Christian son of the pagan King Penda of Mercia) and his wife St Ermenilda, herself daughter of Eorcenberht the King of Kent. She obtained her father's consent to enter the Abbey of Ely, which had been founded by her great aunt Etheldreda (or Audrey), the first Abbess of Ely and former queen of Northumbria, whose fame was widespread. Werburgh was trained at home (traditionally by St. Chad, afterwards Bishop of Lichfield), and by her mother; and in the cloister by her aunt and grandmother. Werburgh was a nun for most of her life. The shrine of St Werburgh remained at Hanbury until the threat from Danish Viking raids in 875 prompted their relocation to within the walled city of Chester. A shrine to St Werburgh was established at the Church of St Peter and St Paul (the site is now occupied by Chester Cathedral). There were two significant revivals of the cult, first with her promotion at Chester by Æthelflæd and second when the Norman Earls of Chester funded the Abbey which would later become Chester Cathedral.

Alfred's archbishop Plegmund is believed to have lived near Chester for a while and gives his name to a holy well at Plemstall. Chester retained its importance as a religious and political center, with Edgar the Pacific being crowned both at Bath and at Chester (in 973) as the first king of all England. The religious rites used in his coronation (use of anointing etc.) were devised by Dunstan and have been in use ever since. Two early churches in Chester: St Bridget and St Olave would appear to have had connections with the pre-Conquest Irish and the Viking populations respectively, and local legend holds that any early inhabitant of the Hermitage was none other that Harold II, who had survived Hastings and become a religious recluse.

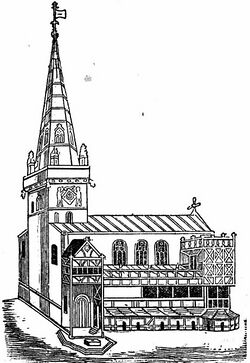

Following the conquest the Normans made a number of changes to the church. A more centralised system was put in place and most Anglo-Saxon bishops and archbishops were removed. Peter de Leia, bishop of Lichfield (consecrated in 1067) relocated his episcopal see to Chester in 1075 during the Earldom of Hugh of Avranches. One theory as to why this was done is that the bishop saw some scope for extending his bishopric into North Wales, which was then being conquered by Hugh. Another reason is given by Henry de Knyghton - a council was held in London, under the presidency of archbishop Lanfranc, at which it was deemed expedient to ransfer the sees of the Bishops from villages and small towns to more significant towns. The old St John's just would not do as the home of an important bishop, and so had to be rebuilt. The bishop's seat did not stay in Chester, but St John retained Cathedral-like ambitions for its architecture.

Medieval

Chester's relics of the Medieval period include two Cathedrals and the Chester Mystery Plays. The Cathedral was previously a Benedictine Abbey founded by the Normans. The prior collegiate church dedicated to Werburgh appears to have been razed to the ground around 1090, with the secular canons evicted, and no known trace of it remains. It was an enterprise in which the Norman Abbey of Bec was much involved. The Norman Earl Hugh of Avranches' closest friend among the higher clergy, the prelate chosen to dedicate his new foundation, was Anselm, abbot of Bec, soon to become archbishop of Canterbury. The first abbot of Chester, Richard (1092–1116), was a monk of Bec and according to Ranulf Higden had been Anselm's chaplain. Higden was one of the important monastic writers from Chester, being the author of the Polychronicon. Other writers associated with Chester include Lucian the Monk and Robert of Chester and Henry Bradshaw.

Although Chester had few parish churches for a town of its size, it was home to several religious communities which played a correspondingly large role in town life. Their precincts were extensive, and their inmates formed sizeable and occasionally troublesome groups within the population.The Dominicans (Blackfriars) were established in Chester by 1237 or 1238 when the appearance of the Greyfriars (Franciscans) alarmed their patron, Alexander Stavensby, bishop of Coventry and Lichfield. So vehement was his reaction to the prospect of the two orders competing for alms that he has been thought responsible for establishing the Dominicans in Chester, although there is no definite evidence and it is equally possible that they came there under the patronage of Ranulph III, earl of Chester. The Whitefriars (Carmelites) were established in Chester by 1277 when they were given alms for food by Edward I, it was some years before they acquired a permanent home. By the later 15th century the friars were frequently involved in disorder in the town. The Carmelites were especially unruly. In 1454, for example, three of their brethren were charged with wandering armed through the city to the terror of the populace, and in 1462 another was bound over for feuding with a monk of St. Werburgh's. Most scandalously of all, throughout the 1490s the entire community, including the prior, appears to have taken part in a succession of brawls and internal disputes. The other friaries were not immune from such problems. In 1454 the prior of the Dominicans and several of his brethren attacked a servant of Abbot Richard Oldham, who as bishop of Man had held ordinations in their church in 1452. The feud with Oldham evidently continued, and members of the community, including another prior, were bound over to keep the peace in 1459, 1462, and 1463. In 1464 one of the friars was accused of murdering a baker outside the friary gate, and the prior of abetting him. In the 1490s the prior was involved in an affray against the prior of the Carmelites, and in 1510 or 1511 one of his successors was accused of assault. Even the Greyfriars had their share of trouble: their prior was attacked in 1427, and one friar was accused of assaulting another and a second man in 1502 or 1503.

The religious community which enjoyed closest relations with the citizens was the collegiate church of St Johns. Staffed by a dean and seven canons whose liturgical duties were generally performed by ill-paid vicars choral, from the 13th century it was the citizens' favoured church for burial and chantries. From the late 13th century the most significant relic in Chester was the Holy Rood at St Johns, a silver-gilt crucifix supposedly containing wood from the True Cross. Its origins are uncertain. Perhaps it was brought from the East by Earl Ranulf de Blondeville, who was on Crusade in 1219-20 - or perhaps it is associated with the legend of a cross from Harwarden which floated up the River Dee. The relic's fame extended well beyond the city. In the 14th century the oath "by the rood of Chester" was evidently commonplace, being mentioned in both William Langland's great poem the Vision of Piers the Ploughman and the less famous Richard the Redeless.

By the early 13th century the city had received its full, if comparatively modest, complement of nine parish churches. Besides St. John's and the monks' parish of St Oswald, they comprised the churches of St Mary on the Hill, Holy Trinity, St Peter, St Michael, St Martin, St Bridget, and St Olave. The early history of many of these is poorly understood. By the 1250s there was also a chapel dedicated to St. Chad in the Crofts, though it is uncertain whether it was ever parochial. The mother churches' monopoly over burial rights appears to have persisted until relatively late, and there were evidently no graveyards at the other churches until the 14th century. The first seems to have been at St. Mary's, the only church apart from St. Oswald's to have a large parish outside the city liberties. The evolution of the parishes and the final shape of their boundaries have been plausibly explained as the successive subdivision of territories attached to the two oldest foundations, St. Oswald's and St. John's, as new churches were established from the 10th century onwards.

Chester had relatively few religious guilds and their impact upon city life was correspondingly limited. In the early 14th century the guild of St. Mary comprised some 48 members of the civic élite, but its purpose is unknown and it was probably short-lived. Thereafter the city never had more than three confraternities. The earliest and most important was that of St. Anne, probably founded in 1361, when its members successfully petitioned the Black Prince for a licence to hold lands and rents in Chester to maintain a chantry and two chaplains in St Johns church.

The Chester Mystery Plays are traditionally dated about 1325 (or 1327), but a date of about 1375 has also been suggested. Chambers also gives a date of 1208 but notes that date may be too early. Some early writers expressed the view that they were written by Ranulf Higden (c.1280 - c.1363), author of the Polychronicon, as stated in the Prologue to the plays. Whatever their actual date, it is clear that as early as 1533 they were regarded as old beyond living memory. Chambers eventually fixed on a date of 1328 which was accepted for many years, and from which it appeared that the Chester plays were the earliest surviving mystery plays. Later reserach showed that Chambers date was based on myths and mis-statements from a proclamation from around 1531/2 and the likely date for the current text of the plays dates from around 1532 with earlier versions of some or all of the plays being performed as far back as some time before 1422. It would appear that much of the text of the plays is derived from "A Stanzaic Life of Christ" which was itself based on Higden's Polychronicon and the "Legenda Aurea". The "Life" was written by a monk of St Werburgh's, Chester, and was a clear influence on the Chester mystery plays.

Reformation

The Midsummer show, later the Midsummer Watch Parade seems to have originated 1498-9 when Chester was visited by Prince Arthur visited the city with his page Thomas Cowper, although the visit was apparently from August 1498 until September of the same year. Thomas Cowper was Page of Honour to Prince Arthur (19/20 September 1486 – 2 April 1502), Prince of Wales, Earl of Chester and Duke of Cornwall. As the eldest son and heir apparent of Henry VII of England, Arthur was viewed by contemporaries as the great hope of the newly established House of Tudor. His mother, Elizabeth of York, was the daughter of Edward IV, and his birth cemented the union between the House of Tudor and the House of York. Plans for Arthur's marriage began before his third birthday; he was installed as Prince of Wales two years later. At the age of eleven, he was formally betrothed to Catherine of Aragon (see: Leche House), a daughter of the powerful Catholic Monarchs in Spain, in an effort to forge an Anglo-Spanish alliance against France. Prince Arthur's early death would be one cause of the Reformation.

The dissolution of the monasteries was much the same land-grab by the gentry as it was elsewhere. However the situation in Cheshire was in some ways unique because of the county's Palatinate past and a degree of independence from the rest of England. Ever since the Crown annexed the earldom in 1237, the integration of the Palatinate with the nation had been under way. But it was the sixteenth century which saw the decisive conclusion, after which the men of the county, or at least the elite, accepted that they were part of the English political nation. This was not to be the end of it: family feuds over both politics and religion would continue into the Civil War and linger on as the Jacobite cause.

There are probably many reasons why the medieval Mystery Plays were banned, with the Chester Mystery Plays possibly having the most complex reasons. Among these may be the impact of prophecy on the politics of the somewhat fragile Elizabethan state, and on earlier administrations. Starting with the Octavian/Augustus prophecy depicted in the Chester Nativity a whole string of prophetic utterences and writings can be interlinked down to the time of Elizabeth Tudor. Many of these are so vague that just about any interpretation can be placed on them. Some relate to "savior kings", "returning kings" or "boy kings" and would have been familiar to the audience for the plays. A few instances stand out, such as Monmouth's unfortunate creation of a Celtic Arthur myth prior to both Welsh revolt and the birth of a "new" Arthur of Brittany. Garbled history which made Constantine half-English and mixed-in the tale of Macsen Wledig, together with a confusion of Helen of Constantinople and Elen of Caernarfon added more source-material for myth-mongers. Anyone who wanted to create a particular interpretation of the existing myths had a very broad pallet to work with. The Tudors themselves had manipulated myth from the landing of Henry Tudor and his march through Wales flying an "Arthurian" flag, but later sought to bring all prophetic and potentially sorcerous activity under state control with new laws. In the end, Elizabeth the last of the Tudors herself became mythologised by Edmund Spenser in 1590 as The Faerie Queene, although even that has in Book I Lucifera, the "mayden Queene, that shone as Titan’s ray" whose brightly lit "House of Pride" masks a dungeon full of prisoners.

The mention of "Santa Maria in Ara Coeli" in the Chester Nativity was clearly recognised as a potentially sensitive issue, as both the comments in the Banns and the words of the Expositor show. Under the reign of Elizabeth, native Cestrians inevitably faced a conflict between loyalty to their Roman-founded heritage and their English monarchy. In some ways the plays can be seen as a scripted exercise in which doubt is first exposed and then removed, and that made them particularly open to attacks by the likes of Protestant zealot Christopher Goodman, who appears to have a distinct blindness for nuance. For reasons that can now only be speculated upon the custodians of the Chester scripts chose to retain the reference to the church of Santa Maria while attempting to explain it away. Similarly, the response of the audience (both Welsh and English) to this mention of prophecy can only be guessed at. It is possible to speculate about plots and propaganda, but the truth will probably always be lost. Prior to the Enlightenment people inhabited a world in which myth and religion largely replaced the supposed historical and scientific truth of today. However, seen in one light, these were and remain for the majority just recieved knowledge.

Elizabethan Chester

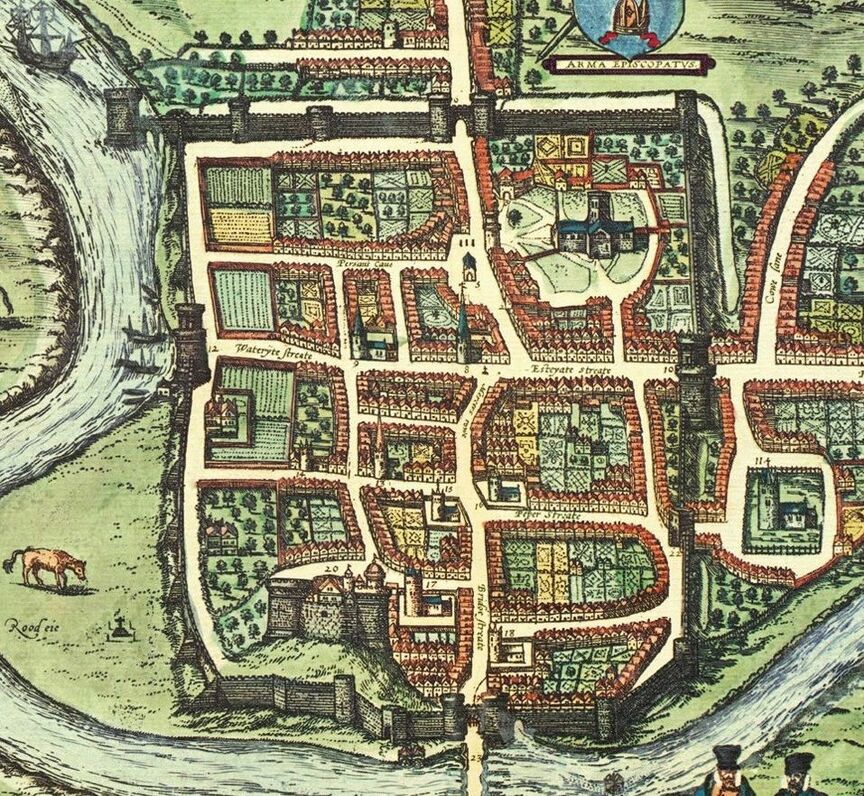

Explore Queen Elizabeth I's Chester as it was in 1651 (without the plague, fear of robbery or having a building fall on you) "mouse-over" on the map below will reveal various locations. Clicking on a location will reveal more detail.

Civil War

The Civil War had many causes but religion was one reason for the strife that set neighbours and close relatives against each other (see: Cholmondeley). Cheshire was very much a divided county, even though efforts were made to broker a local truce in the form of the Bunbury Agreement. The Bunbury Agreement of December 23, 1642 was drawn up by some prominent gentlemen of the county of Cheshire to keep Cheshire neutral during the English Civil War. It proved to be a forlorn hope. Prior to the outbreak of the Civil War there had been a "pamphlet war" in Cheshire, which slowly progressed to further violence. In the midst of this was the iconoclast John Bruen and his family, as well as the puritan William Prynne. The scene of many events leading up to the Civil War was the High Cross outside of St Peter in the center of the city, while St Peter, on the site of the Legionary Headquarters and shrine became something of a center for the puritans. The seat of the civil administration of Chester was the "Pentice" a lean-to building constructed on the frontage of St Peter.

Chester's High Cross did not survive the Civil War. The Cross was first mentioned city records in 1387. It has been the site of public proclamations since medieval times. The earliest known official mention of Chester's Town Crier at the Cross was a famous proclamation by a 15th century Crier. In the 17th century, the Town Crier was permitted to have a stall at the Cross and take the profits. In 1594 a gibbet was erected at the high cross to encourage good behaviour on the part of troops being shipped to Ireland.

During the Civil War, the Cross had served as a rallying point for the Royalist citizens, but after their eventual surrender to Parliamentary forces at the end of the siege in 1646, it was feared they would destroy it, an iconoclastic ordinance of 1643 having called for the "utter demolishing of all monuments of superstition and idolatry". After their surrender, the citizens had received reassurances that "no church within the city, evidences or writings belonging to the same shall be defaced" and assumed this also applied to the Cross. They were wrong, and it was demolished in 1646. According to the "official version", the ornate top section, with its carved figures of saints, apostles and the Virgin Mary, vanished without trace. The base of the Cross ended up, around 1817, at Plas Newydd in Llangollen, North Wales, where it remains to this day. The remainder was hidden under the steps of nearby St Peter's Church, and stayed there forgotten until it was rediscovered, as some say, in 1820, during the course of repairs. A churchwarden (other version differ) placed the pieces in his garden in Handbridge, until they were acquired by the 1st Duke of Westminister some 60 years later, who had them placed in the newly-opened Grosvenor Museum. However, a drawing of Overleigh Hall, home of the Cowper's, shows what may be the High Cross located near that building: see Brown for more discussion of this. The city council re-erected the Cross in the Roman Garden in 1949, but, with the coming of pedestrianization, it was restored to its ancient original site at the intersection of the city's main streets in 1975, after an absence of some 329 years.

Chester played a part in the religious dissent which followed the death of Charles II. James II was in some ways an apparently tollerant monarch and heard Quaker William Penn speak at Chester (possibly in Frodsham Street). Shortly before the "Glorious Revolution", while James II was in Chester he made his famous speech in which he said:

- "suppose... there should be a law made that all black men should be imprisoned, it would be unreasonable and we had as little reason to quarrel with other men for being of different [religious] opinions as for being of different complexions."

He was far ahead of his time - so he had to go. Chester was one of the few places where there was any resistance to the "invasion" by William of Orange: in 1688, the Roman Catholic lords, Molyneux and Aston, raised a force, and made themselves masters of Chester Castle, for James II - but his abdication rendered further efforts useless.

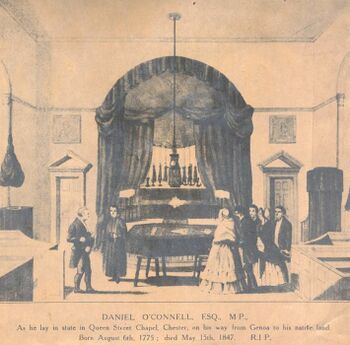

Catholics and Non-conformists

Despite being a cathedral city and a magnet for the region's Anglican establishment, Chester was fertile ground for religious nonconformity from the later 18th century. Old Dissent had largely withered away by 1750, leaving only small groups of Baptists and Quakers besides the larger Matthew Henry congregation based in Trinity Street. From the 1770s, however, the Congregationalists were growing rapidly in strength and respectability. Methodism, too, had taken hold in the 1740s and continued to widen its appeal, not least through John Wesley's frequent visits to Chester on his journeys between England and Ireland. The greater diversity of worship on offer by 1800 must have been fuelled in part by the increasing number of migrants to Chester. In particular, Roman Catholicism in the city was almost exclusively an Irish phenomenon. Until the 1750s there was no permanently resident Roman Catholic priest in Chester, masses being said either by a gentleman's chaplain, typically from Hooton Hall in Wirral or the Fitzherberts' house. The first purpose-built chapel was opened in Queen Street in 1799 and numbers rose slowly before the Famine and rapidly afterwards, reaching an estimated 2,000 by 1889. The present focus of the Catholic community is St Werburgh's in Grosvenor Park Road.

By 1851, in the midst of an economic boom and with heavy inwards migration from Cheshire, Wales, Ireland, and elsewhere, levels of religious worship in the city were relatively low. Probably not much more than two fifths of the population went to church or chapel on Census Sunday. The principal chapels except the Quakers and Unitarians joined forces to form the Chester Evangelical Free Church Council in 1897. Its main activities before 1914 were campaigns against the races (specifically gambling) and Sabbath-breakers, and an ambitious plan to divide the city into nonconformist "parishes" for a common missionary effort. The various groups were not without some rather comedic events: the Rev Philip Oliver (1763-1800), an early methodist and descendant of John Bruen - the Chester Puritan who was noted for smashing-up various local village crosses - was given notice to quit for his over enthusiastic bell-ringing. The Congregationalist pastor, Ezra Johnson, sold the chapel to the Welsh Baptists, allegedly without the consent of the trustees, and the congregation evidently dispersed in acrimony.

The main nonconformist groups may have peaked before 1900. Membership of the Wesleyan Methodist circuit fell from 588 in 1883 to 429 in 1910 and a mission to Hoole collapsed in the 1890s. In contrast, fringe groups were proliferating between 1900 and 1914: a second Mormon missionary effort was begun, the Brethren fragmented, and for the first time there appeared small groups of Swedenborgians, Spiritualists (of two varieties), and Christian Scientists.

Exploring the History

Sites particularly associated with the religious history of Chester are listed below. There is also an extensive collection of Roman Tombstones in the Grosvenor Museum. The tour of the tower at Chester Cathedral is excellent on a clear day, with extensive views over the Cheshire plain and access to parts of the Cathedral that are seldom seen. St Johns has spectacular architecture and can be taken-in as part of the peaceful (and unofficial) St Johns Trail.

Sources and Links

- Churches and religious bodies: Medieval parish churches in Chester, at British History Online;

- Later medieval Chester 1230-1550: Religion, 1230-1550

Pages in category "Religious History"

The following 48 pages are in this category, out of 48 total.