Richard of Avranches

Richard (1101-1120: Second Earl - drowned)

(Kings: Henry I)

Summary

Born in 1094, he was seven when he inherited his father's vast estates (1101). In 1120, aged 26 he was drowned on the wreck of the White Ship.

- Parents: Hugh of Avranches and Ermentrude of Claremont (b.1058 - d.after 1106)

- Spouse: Richard married Lucia-Mahaut, daughter of Stephen, Count of Blois (her brother was to become King Stephen)

- Children: none (succeeded by Ranulf de Meschines)

Minority

Richard's mother is something of a mystery. She is said to have been the daughter of Hugh I of Clermont, Lord of Clermont-en-Beauvaisis and of Luzarches and Marguerite de Ramerupt, Dame de Roucy. She was apparently born in 1058 (or 1055 according to some sources), which would put her in her late 30's in 1094 when Richard was born. This seems remarkably old to bear Hugh's first child, especially given that by this time Hugh had supposedly grown so fat that he could "barely crawl about". Her date of death is given by some sources as 1101 although she appears to have been signing charters as late as 1106 (when she signed one confirming the grant of land in Abingdon). The date of her marriage to Hugh is only given as "before 1093", but that is probably based on the assumption that Richard was legitimate. For such a skilled politician Hugh seems to have been remarkably lax in his familial duty to produce an heir.

Given the immense power and political adroitness of Hugh it was possible that his heir could have been a major threat to the Crown (especially if a legitimate son had been born earlier). However when Hugh died the new king Henry I had little to fear as Hugh's successor was a youth of seven years. Henry worked out how to deal with this, he all but adopted the child and sent him off to Normandy to be educated with his own children, conveniently obtaining a more-or-less free hand with the young Earl's lands during his minority. Indeed, even after he came of age Earl Richard appears to have prefferred to remain in Normandy and enjoy society leaving the supposed Palatinate to become what was effectively a royal-fief. The very fact that Crown appointees managed his estates rather than some form of "regency" illustrates that the Palatinate was not the quasi-independent state that some have claimed it to be.

In consequence, Richard's companions would have include the king's son William Adelin (5 August 1103 – 25 November 1120), who was, according to Henry of Huntingdon, "a prince so pampered" that he seemed "destined to be food for the fire". The friendship would turn out to be fatal for Richard.

Earl Richard

In 1114 (aged 20), together with Alexander I of Scotland, Earl Richard led an Anglo-Norman army into Gwynedd as part of a three-pronged campaign organised by Henry I of England against Gruffydd ap Cynan. The Welsh King satisfied the English King with an oath of homage and a suitable fine. The campaign soon fizzled out after the oath-giving, without combat, allowing Richard to return to Chester, while Geuffydd lost no land in the conflict.

Suspicious Charters

Earl Richard, gave little to Chester's Benedictine abbey during his short earldom; apart from the grant of a mill on Flookersbrook at Bache, his gifts were restricted to the city and its suburbs. Ranulf's great charter of 1151 confirms in detail the gifts made to St Werburghs Abbey by his predecessors and their barons and other donors, followed by a statement of his own gifts and those of his barons. The original is at Eaton Hall MSS No 1.

- Post obitum HUGONIS comitis Ricardus comes filius eius dedit pro anima illius deo et sancte Werburge terram Wlfrick prepositi foris portam de North, et molendinum de Beche, et tres mansuras quitas et pactas, duas in civitate et unam extra murum. Teste Willelmo constabularia, Walterio de Vernona, Radulfo dapifero et alis multis.

- After the death of Earl Hugh, Earl Richard his son has given for his soul, the land which was Wulfrics against the Northgate, to the Abbot of St Werburgh and the mill of Bache, and three dwellings of free and quiet, two in the city and one outside. Witnessed by William the constable, Walter de Vernon and Rudolf the steward.

Ormerod has a slightly different text:

- Ego comes Ricardus post obitum patris mei dedi pro saluta animae mea et suae terram quae fuit Wulfrici praepositi foris portam de North, prius per unam spicam frumenti deinde per unum cultellum super attare Sanctae Werburgae: et molendinum be Bache : et tresa mansuras quietas et ab omni re liberas, duas in civitate et unam extra portam de North...

- Earl Richard, after the death for my father, have given, for the welfare of my soul and of his, the land which was Wulfrics over against the Northgate, by service of first an ear of corn and afterwards of a knife or sickle upon the alter of St Werburghs : also the mill of the Bache, also three messuages free from all dues, two being in the city and one outside the Northgate

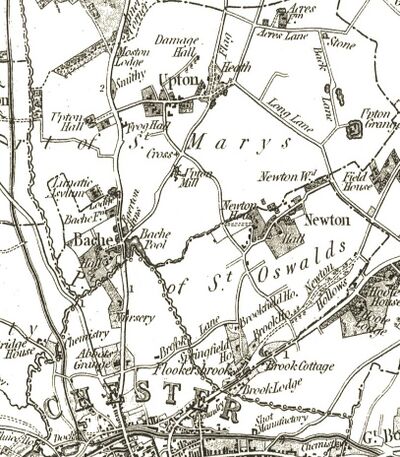

There is no sign of the mill today, or the millpond, but it was located where the Bache Brook (Flookersbrook) crossed Liverpool Road. However a little investigation reveals that this charter may not be all that it appears. The earliest known owner of land at Flookersbrook was Arni of Neston (see: "Open Doomesday") - and his lands passed to William son of Nigel, or fitz Nigel. Arni is possibly a Viking name, and it has been suggested, in "Viking Wirral" that his burial place is at "Arnehow" at Oxton - now a park known as "The Arno".

William FitzNigel is probaly the same who succeeded his father Nigel as baron of Halton and Constable of Chester. His gift to St Werburgh’s of "Neutona" (Newton by Chester, a manor of 1 hide) with the service of Hugh fitz Udard, was included in the almost certainly forged confirmation of Earl Richard dated 1119 (Barraclough, Charters of the Earls of Chester, 14–16, no. 8)[1]:

- "Willelmus constabularius dedit Neutonam simul cum servicio Hugonis filii Udardi de quatuor bovatis, et cum servicio Wiceberni de duabus bovatis."

"Udard" or "Odard" is often said to be the ancestor of the Duttons, but there is considerable doubt about much of the ancestry of Cheshire gentry. The arguments that this charter is a forgery hinge on the fact that there seems little reason for a young earl of 25, who in 1119 could not have known he was to drown the following year in the wreck of the "White Ship", to draw up such a convenient list of donations to the church made "in meo tempore ecclesie sancte Werburge Cestrie" ("in my time to the church of St Werburgh of Chester"). Also, Richard was in Normandy from October 1118 and for most of 1119 and into 1120. Richard did spend some time in England, but monks are sometimes notorious for faking grants of land.

There was a tradition in the abbey that Richard quarrelled with the abbot over the manor at Saighton and that he 'intended to alter and change the foundation of the said abbey to another religion' and that this was only prevented by his providential death in the White Ship; there may be some substance to the story as the abbacy was left vacant during the last three years of Earl Richard's life.

A curious tale is told of Richard by Bradshaw, a monkish writer who is often innaccurate. Richard, on his return in 1119, from Normandy, where he had been educated, undertook a pilgrimage to the well of St. Winifred, and that, either in going or returning, he was attacked by the Welsh, and compelled to seek refuge in Basingwerk Abbey. In this "insecure retreat", continues Bradshaw, Richard applied for relief to St. Werburgh, who miraculously raised certain sands in the estuary of the Dee, between Flintshire and the promontory of Wirral in Cheshire, which enabled Richard's constable (William fitzNigel) to pass over to his assistance; and the sands said to have been thus formed, have to this day borne the designation of "the Constable's Sands." The story is interesting because most sources claim that Basingwerk was only founded in 1132 by the later earl Ranulph De Gernon.

Many of these early tales may have been made up by later writers to provide evidence of grants of land or other property to the Church

The White Ship

King Henry I had at least a dozen children, but only two were with his wife Matilda of Scotland, a daughter also named Matilda and a son named William Adelin (Atheling). The rest of his children were born to his mistresses, although Henry treated his illegitimate sons and daughters very well and gave them important positions in his government. William, as his only legitimate son, stood to inherit his kingdom. With the recent agreement between Henry and the French king, and the marriage of William with Matilda of Anjou a daughter of Count Fulk V of Anjou a year earlier, it now seemed that his son would face no obstacles in inheriting the Anglo-Norman empire.

The line of the d'Avranches as Earls of Chester failed when Hugh's son Richard, with his illegitimate half-brother Ottuel, joined the young prince William Adelin (heir to Henry I) aboard the doomed White Ship on 25th November 1120. The ship foundered, drowning all but one, and Richard died aged 26, leaving no issue. William of Malmesbury wrote:

- "Here also perished with William, Richard, another of the King's [Henry I] sons, whom a woman of no rank had borne him, before his accession, a brave youth, and dear to his father from his obedience; Richard d'Avranches, second Earl of Chester, and his brother Otheur; Geoffrey Ridel; Walter of Everci; Geoffrey, archdeacon of Hereford; [Matilda] the Countess of Perche, the king's daughter; the Countess of Chester; the king's niece Lucia-Mahaut of Blois; and many others..."

Richard was married to Lucia-Mahaut, daughter of Stephen, Count of Blois. This particular Count of Blois was also the father of the Stephen who was to later become the English King and who was due to sail on the White Ship as well. Whether the events surrounding the White Ship will ever be completely clear is in doubt. The younger Stephen of Blois (later King Stephen - also Henry I's nephew and the person with the most to gain from the sinking), made his excuses and left, either because he had an attack of diarrhoea or because of outrage at the drunkenness on board. Apparently, the wreck of the ship was in part the fault of Richard of Lincoln (illegitimate son of Henry I of England), who had urged the owner, who was also the captain - (Thomas FitzStephen) - to sail at full speed, despite the darkness of the night in an attempt to catch up with the rest of the fleet. The captain was the son (some say grandson) of Stephen FitzAirard (Estienne filz Airard) who had been captain of the ship "Mora" for William the Conqueror when he invaded England in 1066.

The White Ship was the Titanic of the Middle Ages, a much praised vessel at the forefront of technology and on its maiden voyage (after a refit). It was wrecked against a foreseeable natural hazard in the reckless pursuit of speed suggested by an influential passenger, while sailing in the moonless dark. The passengers constituted the cream of high society, thrown into the chilly waters with insufficient lifeboats. William of Westminster writes as follows (conveniently getting the date wrong and putting the whole thing down to the wrath of God):

- A.D. 1120. On the nineteenth of March, the light fell twice on the tomb of the Lord. The same year, king Henry, having subdued all his enemies, and arranged everything in Normandy according to his pleasure, found that joyful things were not to be unmixed with sad ones in this world. For, when his sons William and Richard, and his daughter and niece, and Richard, earl of Chester, and the stewards, and chamberlains, and cupbearers of the king, and many other nobles with them, were sailing joyfully to England, they were all wrecked at sea, and died by drowning, on the twenty-fifth of December, miserably, yet not so as to be pitied ; for their lives had been devoted to irreligious licentiousness. On which account, it is considered that they perished thus in a moment by a strange accident in a most tranquil sea.

Apparently not only were the passengers drunk but also most of the crew. In his account of the disaster, chronicler Orderic Vitalis claimed that when the Captain Thomas FitzStephen came to the surface after the sinking and learned that William had not survived, he let himself drown rather than face the King (The accuracy of this account is debatable - it describes a full moon, but an ephemeris shows that the moon was new that night). Other souces note that William was a young man on whom many hopes rode, nicknamed ‘the Aetheling’ (an Anglo-Saxon title), because his mother Edith-Matilda was descended from The House of Wessex - so he was a part-Saxon heir to the Normans’ empire. One source even suggests that prince William together with a few friends, had initially managed to get aboard the ship's single "life-boat" and were heading ashore. In this version they heared the cries of William's sister (Matilda, Countess of Perche) and returned to save her, only for the boat to capsize drowning all hands. According to Orderic Vitalis, Berold (Beroldus or Berout), a butcher from Rouen, was the sole survivor of the shipwreck by clinging to the rock upon which the ship had foundered..

Richard’s role as earl of Chester was to ultimately keep the northern Welsh kings under Henry I’s rule and to make sure the border was secure. Richard, like his father, led several successful campaigns against the Welsh, most significant were his with King Alexander I of Scotland. Richard’s death presented the Welsh with an opportunity to abolish the Norman’s entrance into northern Wales and secure it for themselves, and in 1121 the Welsh marched on Chester and took advantage of the earl’s death. The Symeonis Dunelmensis Opera et Collectarea reads:

- "The sons of the Welsh king heard about the drowning of Richard Earl of Chester and set fire to two castles, killing many. Some places of the county were heavily plundered".

The attack was led by Maredudd ap Bleddyn with three of Cadwgan ap Bleddyn’s sons. Although rebellions by the Welsh were not uncommon, they were usually dealt with swiftly by the respective earls but as Richard’s death was the catalyst, Henry may have felt the need to make an example of this rebellion. Henry led a substantial army into north Wales in June 1121, and although the king’s army was attacked by a group of archers with Henry himself being hit, it could have been a bloody battle but Henry demanded his army settled and arranged a meeting with Maredudd. The negotiations ended with Henry leaving Wales with gifts and hostages paid by the Welsh prince. When Henry I died in 1135 the Welsh saw that there was a succession crisis looming and revolted again.

The White ship disaster was a catalyst for many devastating events which would shape the twelfth century and beyond. The succession crisis led directly to the period of history known as "The Anarchy". As William of Malmesbury wrote:

- "no ship that ever sailed brought England such disaster, none was so well known the wide world over"

Murder?

Victoria Chandler wrote the article “The Wreck of the White Ship: A Mass Murder Revealed?” in which she suggests that it was possible that someone deliberately steered the boat into the rocks outside of Harfleur. One obvious suspect would be Stephen of Blois, partly because he left the ship just before it launched, and partly because eventually he would be the one to get the most benefit from the tragedy. King Henry I would have no future legitimate male heir. When he died in 1135 his daughter Matilda was supposed to become the next ruler, but Stephen managed to get the support from the Anglo-Norman nobles and become King. However, Chandler dismisses this motive, as even with the death of William the Atheling it would have been very unlikely that Stephen would have a claim to the throne, and that King Henry, who was a prolific father, had still many years to have more children. Chandler finds that another man stood to make great gains from the disaster: Ranulf de Meschines (Ranulf Meschin). He was a nephew of the Richard, Earl of Chester, one of the most important nobles in the Anglo-Norman realm. Earl Richard was aboard the White Ship, as well as several other family members. If they would all die, Ranulf Meschin would be able to claim this inheritance.

Ranulf was on board King Henry’s ship when it left Harfluer. Chandler writes:

- Ranulf would have needed a co-conspirator on the shore and he had a good one. Among those who, like Stephen [of Blois], disembarked before the ship sailed, was William of Roumare, son of Roger fitz Gerald and Lucy of Bolingbroke. After his father died during William’s childhood, his mother had married as her third husband – Ranulf Meschin. Perhaps William and his stepfather saw which passengers were boarding which ships that November day and realized they had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, a chance to acquire the earldom of Chester and, as a bonus, to confuse the royal succession, creating a situation for the future in which the holder of such a massive lordship could be a kingmaker.

However, a third person was needed:

- “an agent on board who could have arranged for the rowers to be drunk and easily misdirected. The identity of this accomplice is provided, with extreme subtlety, by the chronicler Orderic Vitalis. Among those on his list of victims was William of Pirou [a royal steward], who was in fact alive until at least 1123. How could have Orderic have made such a mistake? Or was it a mistake? Could he have been trying to draw his readers’ attention to Pirou? Was Pirou on board the ship when it set sail and found a way to leave it without direction?”

We know that William of Pirou was alive because he appeared as a royal witness to a document on January 7, 1121, a document also signed by Ranulf Meschin. His name also turns up as William Pirou "dapifer" (steward) on another charter of similar date (see J. H. Round: The English Historical Review, Vol. 8, No. 29 (Jan., 1893), pp. 80-83). In 1123, Pirou is noted as leaving Portsmouth for Normandy – his name disappears from history afterwards.

Chandler concludes:

- “How wonderfully convenient it is that the twelfth century has provided us with the very model of the modern murder mystery, even down to the final conclusion that the butler did it. Actually it was the steward, but there is no need to quibble. Probably the most intriguing aspect of the study is that, with the exception of a couple of points of conjecture and interpretation, the whole story is true.”

The sinking of the White Ship is referenced in Ken Follett's novel The Pillars of the Earth (1989). The ship's sinking sets the stage for the background of the story, which is based on the subsequent civil war between Matilda (referred to as Maud in the novel) and Stephen. In Follett's novel, it is implied that the ship may have been sabotaged; this implication is seen in the TV adaptation, even going so far as to show William Adelin assassinated whilst on a lifeboat.

Henry I had not helped to ensure a simple succession as he still holds the record for the largest number of acknowledged illegitimate children born to any English king (around 20 or 25). After Henry heard of the disaster, it is said that he never smiled again. Desperate to secure his family's succession, he had the English barons swear an oath to uphold the rights of his only remaining legitimate child: his daughter Matilda who they were to recognise as their Queen after Henry's death. The time had not yet come for a woman to be accepted on the English throne, so when King Henry died (in December 1135), his nephew, Stephen of Blois (grandson of William the Conqueror through his daughter Adela) siezed the crown and four years later, the status quo degenerated into a patchy Civil War generally known as "The Anarchy".

Sources - Richard

- Britannia.com The Wreck of the White Ship

- Victims of the White Ship disaster on Wikipedia;

- Victoria Chandler, "The Wreck of the White Ship", in The final argument : the imprint of violence on society in medieval and early modern Europe, edited by Donald J. Kagay and L.J. Andrew Villalon (1998)

- Robert Lacey, "Henry I and the White Ship" in Great Tales from English History (2003)

- Rossetti's the "White Ship"

- St Winefride's Well homepage - it has been described as the "Lourdes of Britain";